By Ryan Smith

In Part 1 of this series, we saw that:

- Jung, when asked in public, always said he was a Ti (ITP) type.

- There is a “secret” seminar where Jung identifies his Intuition as “superior.”

- Some theorists take this to mean that Jung secretly identified as an Ni (INJ) type.

- Jung was not always honest about his own type assessments in interviews.

Here in Part 2, we are going to present and discuss all of Jung’s statements about his own type.

1915-1916: The Question of Psychological Types

As we saw in Part 1, Jung originally developed typology as a system of only two types (EF and IT) along with his colleague Hans Schmid-Guisan. As with the modern-day (two orientations, four functions) system of typology, this early system also characterized the introvert as retaining a subjective disposition towards exterior occurrences while the extrovert was thought to be more objective in his attitude.

Of the two types available at this time, Jung identified himself as the IT type:

“… as I am one of those people who must a priori always have a viewpoint before being able to enter into something, I could not be assured by simply going ahead in my personal relations …”[1]

“As I belong to that category of people who never take the element of feeling sufficiently into account, as opposed to the intellect [i.e. Thinking] … A man of your kind, however, who is as much devoted to feeling as I am to the intellect …”[2]

So in the EF/IT duality, Jung strongly identifies with the IT type, while regarding his correspondent, Schmid-Guisan, as an equally strong exemplar of the EF type.

1919: Personal Letter to Sabina Spielrein

In the years between 1916 and 1921, the F/T dichotomy was eventually complemented by the discovery of the S/N dichotomy. As a historical aside, there seems to be considerable disagreement as to who discovered this dichotomy. What is clear beyond all doubt is that the Dutch analyst Maria Moltzer gave a talk advocating N as its own function (or “type”) in 1916 (and even Jung credits the discovery of the N function to her).[3] On the other hand, the Jung biographer Deirdre Bair has also made discoveries indicating that the S/N dichotomy could have been discovered even earlier by Hans Schmid-Guisan. Furthermore, Jung’s assistant and personal successor, C.A. Meier, has offered statements to the effect that the S/N dichotomy was in fact discovered or developed by Jung’s lover and fellow Jungian analyst Toni Wolff, going as far as to say that she may have written considerable parts of Psychological Types under Jung’s name.

As I have detailed in previous writings, and as numerous people who were personal acquaintances of Jung have attested, Jung was not above stealing other people’s ideas and passing them off as his own. This makes it hard to determine who discovered or developed the S/N dichotomy, though it seems certain that the honor does not belong to Jung. In my opinion, the idea of N as a function or type was most likely conceived by Moltzer or Schmid-Guisan (or both) around 1916 and then developed into a definite dichotomy by Toni Wolff or Jung (or both) in the period between 1917-1921. This is what the evidence suggests and would moreover fit well with their personal types of ENP (Moltzer and Schmid-Guisan) and INJ (Jung and Wolff) – though strictly speaking, one should not assign such determinative power to typology.

In any case, in 1919, while the four functions/two orientations scheme was being finalized, Jung sent a personal letter to his former patient and lover Sabina Spielrein. Though some writers have suspected that Jung also passed off some of her ideas as his own, I have not personally seen any evidence to that effect with regards to typology.[4] At any rate, in 1919 Spielrein and Jung were living in different countries, yet still exchanged letters from time to time. In one of these letters, Jung reports on the development of his typology, and notes down the following:

“Bleuler and Freud are extravert. Nietzsche and Jung introvert. Goethe is intuitive and extravert. Schiller is intuitive and introvert.”[5]

(It is worth noting that Jung eventually seemed to settle for Goethe as an Fe-N-S-Ti type and Schiller as a Ti-N-S-Fe type, and hence not as Intuitive types, which this letter might otherwise be taken to imply.)[6] With regards to Jung’s own type, however, he simply identifies as an introvert here.

1921: Psychological Types

Although Jung does not explicitly declare his own type in Psychological Types, he does drop a few hints. Under the heading “Summary of the Extraverted Rational Types,” Jung states the following:

“I call the two preceding types [Thinking and Feeling] rational or judging types because they are characterized by the supremacy of the reasoning and judging functions. … But I am willing to grant that one could equally well conceive and present such a psychology from precisely the opposite angle. I am also convinced that, had I myself chanced to possess a different psychology, I would have described the rational types in the reverse way, from the standpoint of the unconscious – as irrational, therefore.”[7]

As usual in the professional writings of Jung, we get that fleeting vagueness and ambiguity of phrase which many of his readers have complained about and which Jung himself would be the first to admit (and even praise) about himself.[8] Certain well-known names in the field of typology seem to have read Psychological Types and come away with the impression that Jung does not identify as any particular type in that book. However, I cannot see how one can take the above passage to mean anything but that Jung identifies as a Thinking or Feeling dominant type in the above passage.

1925: Notes on the Seminar Given in 1925

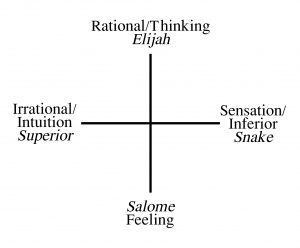

We come now to the infamous Notes on the Seminar Given in 1925, which we also touched upon in part 1 of this series. Here, Jung first identifies as a Ti-S-N-Fe type:

“As a natural scientist, thinking and sensation were uppermost in me and intuition and feeling were in the unconscious and contaminated by the collective unconscious. … Sensation as an auxiliary function would allow intuition to exist. But inasmuch as sensation (in the example) is a partisan of the intellect [i.e. Thinking], intuition sides with feeling, here the inferior function.”[9]

So Jung identifies as an Introverted Thinking type with auxiliary Sensation (of an unspecified orientation).[10] It all seems clear enough, so why the multiple scholarly headaches over Seminar of 1925? Well, for one thing, because later in the seminar Jung identifies as a different type:

“As I am an introverted intellectual [i.e. Thinking type], my anima contains feeling [that is] quite blind. In my case, the anima contains not only Salome [i.e. Feeling], but also some of the serpent, which is sensation as well. …

Feeling-sensation is in opposition to the conscious intellect plus intuition, but the balance is insufficient.”[11]

As noted, Jung used ‘intellect’ as a synonym for the thinking functions (although this parlance is no longer in use today).[12] Concerning the admins’ opinion here on the site, we personally think that all types have the ability to be ‘intellectual,’ and that Jung’s use of intellectual as a synonym for Thinking seems to break the stated aim of crafting a psychological typology in favor of the more straightforward, William James-like approach to typology where mental contents are prioritized over cognitive structures.

In the seminar, Jung tells the story of a dream or vision he had, which supposedly caused his type to change. At any rate, where Jung first said he identified as a Ti-S-N-F type, he now says that he identifies as another type. But which type is implied? Opinions are divided here.

In my assessment, it is clear enough that Feeling is still identified as the inferior function. However, this reading flies in the face of the interpretation of the American typologist John Beebe and others, who have used the passage to argue that Jung’s “new” type after the vision should be that of an Ni-T-F-Se type.[13] As far as I understand it, Beebe et al. base their interpretation on a diagram furnished by Jung himself, which says that after the vision, his Intuition is now ‘superior.’[14] However, in my opinion, Beebe et al. are reading too much into this claim, since ‘superior’ does not necessarily mean ‘dominant.’ Recall, in fact, that in Latin, ‘superior’ merely means above. Square this with Jung’s ubiquitous fondness for Latinisms (and his considerable proficiency with Latin) and the reading that Jung changed his self-assessment from Ti-S-N-Fe to Ti-N-S-Fe seems much better supported by the entirety of the text.

In my assessment, it is clear enough that Feeling is still identified as the inferior function. However, this reading flies in the face of the interpretation of the American typologist John Beebe and others, who have used the passage to argue that Jung’s “new” type after the vision should be that of an Ni-T-F-Se type.[13] As far as I understand it, Beebe et al. base their interpretation on a diagram furnished by Jung himself, which says that after the vision, his Intuition is now ‘superior.’[14] However, in my opinion, Beebe et al. are reading too much into this claim, since ‘superior’ does not necessarily mean ‘dominant.’ Recall, in fact, that in Latin, ‘superior’ merely means above. Square this with Jung’s ubiquitous fondness for Latinisms (and his considerable proficiency with Latin) and the reading that Jung changed his self-assessment from Ti-S-N-Fe to Ti-N-S-Fe seems much better supported by the entirety of the text.

Some readers might then ask why Jung should be cautious to identify as someone whose Intuition was superior to his Sensation, since in modern typology, Intuition is commonly perceived as being more attractive and alluring than Sensation. The answer is that Jung did not view the matter this way. He saw Sensation as being synonymous with empiricism and science, whereas Intuition was a slightly mad form of psychic adaption; one that the younger and middle-aged Jung certainly did not wish to apply to himself. That this is so can be seen, among other things, in Jung’s own phrasing that “as a scientist, thinking and sensation” predominated in him (emphasis added). As the Jung biographer Gary Lachman has pointed out, Jung held grave doubts about his status as a scientist vis-à-vis poet or artist and desperately wanted to be the former. It was not easy for him to square his preference for Intuition with the way he wished to present himself. (Naturally, Jung’s take on typology here implies that one’s vocation dictates one’s type to a very large degree and that type can change –two claims that few modern typologists would agree with.)

C.G. Jung (1934 / published 1988): Nietzsche’s Zarathustra: Notes on the Seminar Given in 1934-1939

Next is Jung’s seminar on Nietzsche. When Jung started developing the theory of psychological types in 1916, he first suspected that he might be the same type as Nietzsche. However, by the time he published Psychological Types, Jung had come to believe that Nietzsche was an Ni-Ti-Fe-Se type (whereas Jung thought of himself as some variant of Ti-dominant type).

In the seminar on Nietzsche, Jung says the following of Nietzsche’s type:

“I have heard of mothers wanting to be paid for their love only too often. Nietzsche had not because he was a man with very developed intuition and intellect [i.e. Thinking], but his feeling developed slowly.”[15]

Now Jung is of course speaking of Nietzsche here, but a logical reading of the above quote entails that Jung is unwittingly implying that he is someone with better Feeling than Nietzsche (“I have heard of X, but Nietzsche had not because his Feeling was undeveloped”). However, as readers of Jung will know, Jung frequently utters statements that, if thought through logically, would imply some conclusion that it is fairly obvious that Jung did not wish to make. So while Jung may technically be saying that his Feeling is better than Nietzsche’s (which was in his opinion tertiary), one should probably avoid taking him at his word here.

C.G. Jung (1957): The Houston Films

Another instance where Jung speaks of his type is found in the Houston Films. Here Jung says:

“I saw first the introverted and extraverted attitudes, then the functional aspects, then which of the four functions is predominant. Now mind you, these four functions were not a scheme I had invented and applied to psychology. On the contrary, it took me quite a long time to discover that there is another type than the thinking type, as I thought my type to be – of course, that is human. It is not. There are other people who decide the same problems I have to decide, but in an entirely different way. They look at things in an entirely different light, they have entirely different values. There are, for instance, feeling types. And after a while I discovered that there are intuitive types. They gave me much trouble. It took me over a year to become clearer about the existence of intuitive types. And the last, and the most unexpected, was the sensation type. And only later I saw that these are naturally the four aspects of conscious orientation.”[16]

The use of past tense adds another layer of ambiguity to Jung’s record. “The thinking type, as I thought my type to be…” But as we have seen, Jung never identified as anything but a Thinking type. So unless the past tense is utilized because he opts to speak of the whole affair of typology in the past tense (which is possible), Jung here adds another trap door or secret escape to avoid professing his type in public. Now why might that be? We will look further into that question in later sections of this series.

C.G. Jung (1959): The “Face to Face“ Interview

In Jung’s televised interview with the BBC, we get what is perhaps the most famous of Jung’s statements on his own psychological type. When asked by the interviewer, Jung answered as follows:

[Interviewer: “Have you concluded what psychological type you are yourself?”]

Jung: “Naturally I have devoted a great deal of attention to that painful question, you know!”

[Interviewer: “And reached a conclusion?”]

Jung: “Well, you see, the type is nothing static. It changes in the course of life, but I most certainly was characterized by thinking. I always thought, from early childhood on and I had a great deal of Intuition, too. And I had a definite difficulty with feeling. And my relation to reality was not particularly brilliant. I was often at variance with the reality of things. Now that gives you all the necessary data for diagnosis!”[17]

The reason Jung refers to himself in the past tense here is fairly clearly because he is speaking of his own type at the time where he was breaking with Freud and coming to terms with this development by writing Psychological Types. So what is important to note is that Jung is not answering what type he is now, at the time of the interview in 1959, but rather what type he was from ca. 1913 (the break with Freud) to 1921 (the publication of Psychological Types).

In spite of Jung’s coy finale – saying that “this gives us all the necessary data for diagnosis” – the statement has nevertheless caused confusion and has of course been endlessly debated. How can we interpret it? It has everywhere been taken to mean that Jung’s two uppermost functions are Thinking and Intuition according to himself, and that his two lowermost functions must be Feeling and Sensation. Yet beyond that, there is wide disagreement. For example, in their “Submission Guidelines” for authors writing on psychological type, the Center for the Application of Psychological Type detail Jung’s type to be “INTP or INTJ,” meaning either a thinking type or an intuitive type.[18]

With regards to Jung’s statement, I propose that the following reading comes closest to what he is trying to say: He identifies as a Thinking dominant type. Being “most certainly characterized by thinking” must trump “having a great deal of intuition too.” I cannot imagine how anyone could in good faith conceive the statement to mean that Jung is here ascribing greater weight to his Intuition than to his Thinking.

As for the next part of the statement – that Jung had a definite difficulty with Feeling and that “his relation to reality was not particularly brilliant” – no one interpretation stands out as more salient than its contenders. The part about his “relation to reality” can either be taken to mean that Jung is identifying as an introvert or that he is denigrating his Sensation function. In my opinion, the latter interpretation makes more sense given Jung’s general mode of expression when speaking about typology.

However, since we have established that Jung identifies as a Thinking dominant type in the first part of his statement, and there is nothing in this second part of the statement of equal lucidity, we should conclude that Jung’s inferior function is Feeling, as Jung himself advises us to do in A Psychological Theory of Types, and indeed, in every other place that he talked about his type besides.[19]

Thus, the function order that Jung professes here must necessarily be: Thinking – Intuition – Sensation – Feeling. It is unclear whether Jung alludes to his introversion or not, so strictly speaking we cannot say that he is identifying as either an introvert or an extrovert in the statement above. However, as Jung has identified himself as an introvert on numerous occasions, both before and after, and never as an extrovert, it is reasonable to couple Jung‘s self-assessment as a Thinking type on this occasion with his consistent self-assessment as an introvert, as he did on numerous other occasions.[20]

So Jung (again) identifies as an introverted Thinking type. The remaining orientations of Jung’s functions go unspecified in the interview, but according to Jung’s own schema of function orientations in Psychological Types, the complete orientation of his functions would be either Ti-Ni-Se-Fe or Ti-Ne-Se-Fe.[21]

(1961): E.A. Bennet’s ‘C.G. Jung’

A short and simple biography of Jung was published by his personal friend shortly after Jung’s death. According to Bennet, Jung read the manuscript and made “many suggestions and corrections”.[22] Bennet’s text, which is supposedly approved by Jung himself, says that Jung has the psychology of the introverted Thinking type.[23]

But then Bennet also says that Jung thought Freud was an extroverted feeling type (a claim which Jung supposedly would then also have approved).[24] As far as we know, however, Jung never thought of Freud as an extroverted feeling type, but rather thought him a Sensation type in A Contribution to Psychological Types in 1913 (if one can even speak of such a type with regards to the state of the theory in 1913).[25] Later still, in the 1950s, Jung revised his assessment of Freud’s type so that he now regarded him an introverted Feeling type, albeit one who falsely pretended to be an “an extraverted thinker and empiricist.”[26]

In other words, while the claim that Jung saw himself as a Ti type is unlikely to raise any eyebrows, there is nothing anywhere in the records to suggest that Jung ever thought of Freud as an extroverted Feeling type. Indeed, as has been revealed with the publication of Jung’s letters, Jung rather thought of Freud as an introverted Feeling type. The type claims in Bennet’s book do not seem reliable, and on the whole it seems more likely that either Jung was negligent in reviewing Bennet’s book or Jung did not really review the whole of the manuscript. Personally, Bennet strikes me as trustworthy, whereas (as even Jung scholars have to admit) Jung’s record is less than stellar when it comes to factual reality and telling the truth. Indeed, for my part, I concur with Freud’s characterization that there is a “kernel of dishonesty in [Jung’s] being.” The most likely scenario, to my mind, is that Jung did approve the book, but did not bank on Bennet telling the public that Jung had actually put his stamp of approval upon the text, but I admit that this is no more than an educated extrapolation.

Conclusion

- Thus, from a review of all of Jung’s statements about his own type, we can conclude that Jung never identified as anything but a Ti type with inferior Fe.

- Jung did, however, identify as Ti-S-N-Fe in early life, an assessment he had changed to Ti-N-S-Fe by 1925.

- However, while Jung never identified as anything but a Ti type, he was always coy and ambiguous in the way he talked about his own type. Some of this ambiguity must be chalked up to Jung’s general lack of conceptual clarity, but even allowing for that, Jung still seems especially reluctant to simply present the details of his self-assessment.

- Many (or perhaps even most) modern typologists hold that Jung somehow identified as an Ni type, since he was “obviously” an Intuitive. The critics are likely correct that Jung is an Intuitive type, but that does not entail that Jung ever said that he was (or thought of himself as such). And as we have seen, none of Jung’s own self-assessments have him identifying as an Intuitive type. In the absence of more textual arguments, the contention of those typologists who hold that Jung identified as an Ni type with inferior Se must be regarded as wishful thinking.

REFERENCES

[1] Jung, in Jung & Schmid-Guisan: The Question of Psychological Types (Princeton University Press 2013) p. 40

[2] Jung, in Jung & Schmid-Guisan: The Question of Psychological Types p. 41

[3] Jung: Psychological Types §773n68

[4] Skea: Sabina Spielrein: Out from the Shadow of Jung and Freud (Journal of Analytical Psychology 2006)

[5] Jung, quoted in Covington & Wharton: Sabina Spielrein: Forgotten Pioneer of Psychoanalysis (Brunner Routledge 2003) p. 58

[6] Jung: Psychological Types §104

[7] Jung: Psychological Types §601

[8] Jung, quoted in Shamdasani: Jung Stripped Bare (Karnac Books 2004) p. 48

[9] Jung: Notes on the Seminar Given in 1925 (Princeton University Press 1991) p. 69

[10] Jung seems to be implying Ti-Si-Ne-Fe; however, in Psychological Types §637, Jung had seemed to imply Ti-Se-Ne-Fe as the general rule.

[11] Jung: Notes on the Seminar Given in 1925 p. 100

[12] Jung: Psychological Types §540

[13] Actually, in Beebe’s system an INTJ (Ni-Te-Fi-Se-Ne-Ti-Fe-Si) type.

[14] Jung: Notes on the Seminar Given in 1925 p. 97

[15] Jung: Nietzsche’s Zarathustra (Princeton University Press 1988) p. 1043

[16] Jung, in McGuire & Hull: C.G. Jung Speaking p. 341

[17] Jung, in McGuire & Hull: C.G. Jung Speaking p. 435-6

[18] CAPT: Submission Guidelines (Capt.org) p. 27

[19] “The one-sided emphasis on thinking is always accompanied by an inferiority of feeling, and differentiated sensation is injurious to intuition and vice versa.” Jung: Psychological Types §955

[20] Of course, given Jung’s qualification that “the type is nothing static. It changes in the course of life,” it is theoretically possible, though highly unlikely, that Jung is conceiving of himself as an extroverted thinker in 1959, and then as an introverted thinker before and after that. A further instance of Jung assessing himself to be an introvert: “After this break I had with Freud … I found myself completely isolated. This, however disadvantageous it may have been, had also an advantage for me as an introvert.” Jung: Notes on the Seminar Given in 1925 p. 25

[21] Jung: Psychological Types §637

[22] Bennet: C.G. Jung (Barrie and Rockliff, 1961) p. viii

[23] Bennet: C.G. Jung p. 18

[24] Bennet: C.G. Jung p. viii

[25] Jung: A Contribution to Psychological Types, included as an appendix to Psychological Types, §880 says: “This is the theory of Freud, which is strictly limited to empirical facts, and traces back complexes to their antecedents and to more simple elements. It regards psychological life as consisting in large measure of reactions, and accords the greatest role to sensation.”

[26] Jung, quoted in Kaufmann: Discovering the Mind: Freud, Adler, and Jung (Transaction Publishers 1992) p. 311