Articles attempting to link Jungian typology to aesthetic preferences have always been popular, but unfortunately many of them are of poor quality, along the lines of “ISTPs like Bloodhound Gang and ESFJs like roses and rainbows.” With the help of a prior study by Joan Evans, D.Litt., we will nevertheless attempt to give an outline of the aesthetic preferences that usually follow a given function.

In doing so, however, we should not forget that Jung said in Psychological Types §895 that type portraits can never apply to all members of a given type. Likewise, Jung’s theory primarily says something about the cognitive functions and not so much about the specific psychic material handled by those functions. Aesthetic preferences are psychic material, not psychic functions. In other words, the relation of functions to aesthetic preferences is correlative at best.

The Psychological Aesthetics of Ne

Written by the CT Admin Team, with inspiration from the work of Joan Evans.

The Ne type sees not what is, but what may be. He is always on the lookout for possibilities in the external situation; anything new and anything about to be fascinates him. He loves shifts and turnarounds in the external situation. He has a quick temperament and he likes to do everything incredibly hastily.

With regards to psychological aesthetics, it is these very same dispositions which may be said to form the quintessential Ne aesthetic: Since the Ne type’s mental processes are ignited from possibilities outside himself, he has a tendency to gobble up any new idea and form it to his own end. Since he must be receptive to new ideas and dramatic turnarounds, he appreciates lightness whereas the Te type appreciates heaviness. And since he likes to do everything incredibly hastily, this translates directly into his aesthetic, prompting him to appreciate works of art which include an unnatural speed. And finally, since the Ne type is always looking to transcend the current reality, the lightness in his favored works of art is often one which points towards transcendence.

The psychological aesthetic of the Ne type may thus be summarized as follows:

- An acute receptivity to new ideas, which he re-shapes with ingenuity

- An unnatural lightness and speed, as if absolving natural external boundaries

- A duality of worldly elegance and supernatural transcendence

We will now go over these in turn.

1. An Acute Receptivity to New Ideas, Which are Re-shaped with Ingenuity

This point is bound to seem unglamorous at first glance: What is this thing about being receptive to ideas, rather than coming up with ideas? “Of course I can come up with my own ideas,” the Ne type is wont to say, and are we not going against the grain when we say that the ENP-types, with their zest for innovation and enthusiasm for ideas, are in fact adopting other people’s ideas to fit their own ends? It would seem so. But such is the disposition of the Ne function: It receives its impetus from the outside; from things that are new and unseen in the external world. In respect to the very first phases of an idea’s coming-into-being, Ne itself is barren, as Socrates would so often profess:

“I am like the midwife in that I cannot myself give birth to wisdom, and the common reproach is true, that, though I question others, I can myself bring nothing to light.” – Socrates, in Plato’s Theatetus, 150b

So what Socrates says is that what the Ne type lacks in pure invention he makes up for in adaptive innovation. This is in accordance with our view of the Ne function. In this way, the workings of Ne may be likened to a hovering cloud of gasoline: It carries within itself the potential for unmatched combustion, but something exterior must ignite it – some spark or flicker from the external world must be added to get the process going. In quite the same way, although Socrates professed to be barren of new ideas himself, he famously likened himself to a midwife, who saw the new ideas of others, seized them to the fullest, and made the most of them. This is no different from the sentiment that Stephen Colbert has expressed in modern times:

“I think one of my strengths [is] my ability to serve other people’s ideas. I’m proud of my ability to understand what somebody else is trying to do.”

Yet seizing upon an idea is not all that the Ne types do. They spontaneously and immediately improvise and innovate about the idea so as to shape it to their own ends. Socrates said that once he had seized upon an idea, he made progress at a rate which seemed surprising to others. The reason for this may well be the Ne type’s propensity towards…

2. An Unnatural Lightness and Speed, as if Absolving Natural External Boundaries

Now you may be thinking that a tendency to adopt others’ ideas to fit one’s own ends isn’t an aesthetic characteristic, but merely a psychological disposition, and in a sense you are right. But in another sense, you are not. For it is this extreme lightness and speed coupled with the aforementioned receptivity to new ideas from the outside that conjoin to form some of the clearest instances of the Ne aesthetic. In music, he favors the swirling thrills of baroque music where the lightness and improvisations speak volumes to him. He revels in its elegant aggression and, unlike the Ti types, the Ne type’s love of that which is not commonly seen (or heard) makes him prone to cherish the use of period instruments in music. (Whereas the Ti type can more often make due with modern instruments playing period music.)

Likewise, regarding the tendency to adopt others’ ideas for one’s own ends, it is in baroque music that we find that remarkable free-spiritedness and creativity where both composer and musician can freely adopt others’ ideas – one composer could freely admit another composer’s tune into his own music, and the musicians and singers were quite free to re-interpret the music as they saw fit.

This inclination to have one’s imagination stimulated by what is unknown and unconventional also carries over to the Ne type’s taste in the visual arts. Here, besides throwing his love upon those paintings that show the same speed as he loves in music, the Ne type is wont to appreciate unusual figures and techniques, yes, even unconventional viewpoints that will allow familiar motives to be seen from unfamiliar angles. Here, Tintoretto’s Last Supper may be said to embody both the speed and elegance as well as the innovation and unconventionality that the Ne type cherishes in his aesthetic. As the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre once said, Tintoretto existed in a state of “total opposition to own time.” The same may be said of the Ne type’s psychological disposition: There is a reluctance to be bound by the ordinary and the obvious.

This inclination to have one’s imagination stimulated by what is unknown and unconventional also carries over to the Ne type’s taste in the visual arts. Here, besides throwing his love upon those paintings that show the same speed as he loves in music, the Ne type is wont to appreciate unusual figures and techniques, yes, even unconventional viewpoints that will allow familiar motives to be seen from unfamiliar angles. Here, Tintoretto’s Last Supper may be said to embody both the speed and elegance as well as the innovation and unconventionality that the Ne type cherishes in his aesthetic. As the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre once said, Tintoretto existed in a state of “total opposition to own time.” The same may be said of the Ne type’s psychological disposition: There is a reluctance to be bound by the ordinary and the obvious.

Claude Monet is said to have painted the same haystack 83 times. To the Ne type, that would be certain death. His aesthetic vision is too unreal for him to bother with mundane landscape for its own sake, or to appreciate portraits merely for their accuracy. There must be something more to the aesthetic of the Ne type; a levitational scheme, a lightness of foot, or above all some movement, real or implied.

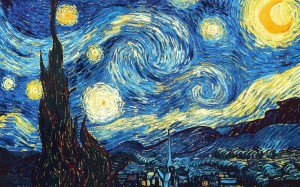

For this reason we may mention ‘levitational’ artists such as Botticelli or Raphael as exemplars of the Ne aesthetic. We may also mention van Gogh where even the inanimate objects in his still lifes seem imbued with a force that could make them dissolve their own form and flow outwards of their own accord.

But the most extreme example of the Ne aesthetic in the arts is found in the works of El Greco. There is hardly a fixed figure anywhere in his works, and everywhere in his oeuvre we find that same speed and lightness which is the hallmark of the Ne aesthetic.

But the most extreme example of the Ne aesthetic in the arts is found in the works of El Greco. There is hardly a fixed figure anywhere in his works, and everywhere in his oeuvre we find that same speed and lightness which is the hallmark of the Ne aesthetic.

If, for example, we look at El Greco’s version of The Agony in the Garden, we see that flamelike light swirls forcefully around the picture. The solid rock behind Christ is not heavy, but light – almost glasslike – as if one could balance it on the tip of one’s finger. And Christ himself seems upwards drifting, as if he were about to leave the ground. Not because of the angel, or some gust of wind, but out of his own intrinsic lightness.

Indeed, this picture of El Greco leads us almost seamlessly to our final point about the Ne aesthetic, which is…

3. A Duality of Worldly Elegance and Supernatural Transcendence

Looking at El Greco’s picture above, you may have noticed that there is not one, but two sources of light: The moon’s natural light and the angel’s supernatural light. This duality may be taken to be an aesthetic illustration of the Ne type’s fundamental longing for the transcendent. It is not immediately obvious why the Ne types should have such a longing, and Ne types may not even recognize that they have it in themselves. But it is nevertheless there and stems from the fact that Ne is bound to always be dissatisfied with the world in its current state. In the words of Isabel Myers, the Ne types “regard the immediate situation as a prison from which escape is urgently necessary.”

A world devoid of the promise of innovation is a world which the Ne type would sooner let go to the dogs. Indeed, as the Ne philosopher Daniel Dennett has written in support of the prospect of creating of biologically enhanced super-humans:

“We may not be up to the job. We may destroy the planet instead of saving it. … [We] have long honored the ‘self-made man,’ but now that we are actually learning enough to be able to remake ourselves into something new, many flinch. Many would apparently rather bumble around with their eyes closed, trusting in tradition, than look around to see what is about to happen.” – Daniel Dennett, Freedom Evolves, Penguin 2004 ed., pp. 5-6

In other words, the risk of destroying the planet is an acceptable risk to take in the service of innovation. The world as it currently exists can be staked on a gamble without further ado. The escape from the status quo is worth more to the Ne type than the world as we know it. For his interest is not in the world as it is, but in the world as it could be. And it is for this same reason that his art should be a dream of something that never was, illuminated by a better light than any light that ever shone before. With worldly elegance on one hand and mystical transcendence on the other, his aesthetic becomes soteriological – a leap into the eye of the storm where he can find peace from the overactivity of his dominant function and his dissatisfaction with the world.

Because of this transcendent element in his aesthetic, the Ne type is less likely to find aesthetic appreciation in sculpture and architecture (which must retain its worldly form) than in painting or music (where no such constraints exist). In the visual arts he rarely appreciates landscape, and when he does, even the landscapes that he appreciates are bound to be depicted as unstable and imbued with vexation and movement, as in the landscapes of van Gogh.

Because of this transcendent element in his aesthetic, the Ne type is less likely to find aesthetic appreciation in sculpture and architecture (which must retain its worldly form) than in painting or music (where no such constraints exist). In the visual arts he rarely appreciates landscape, and when he does, even the landscapes that he appreciates are bound to be depicted as unstable and imbued with vexation and movement, as in the landscapes of van Gogh.

Finally, a word about his colors: With the Te type, the form was above the colors, but with the Ne type, colors are above the form. Indeed, as El Greco has said: “The coloring [of a painting] is more important than the motive.” We suspect that van Gogh would agree.

Perhaps no type takes a more appreciative view of color in his aesthetic than the Ne type. He has an extreme eye for the aesthetic attractiveness of certain colors and where the colors of the Ti aesthetic were often elusive, the colors of the Ne aesthetic are direct but imbued with the transcendental. The color scheme is one of unworldly elegance staring us in the face. As such, the Ne type agrees with Oscar Wilde that:

“All beautiful colors are graduated colors, the colors that seem about to pass into one another’s realm.” – Oscar Wilde, Art and Decoration, Methuen & Company 1920 ed., p. 20

Which is but another way of saying that to an extrovertive, mercurial mind that hungers for stimulation, the same thing should be many things at once.