By Sigurd Arild and Ryan Smith

A lot of myths about Jung and Psychological Types are flying around in the type community, both offline and online. Most prominently, Jung is often held out by people with a superficial knowledge of typology as having written Psychological Types on the basis of his clinical experience with patients and with little outside help. This narrative corroborates the image of Jung as a wise guru and prophet who found these concepts within himself, and indeed Jung himself appears to have labored to confirm this myth in certain interviews and encounters. In this article we propose to debunk some of the claims that often serve as the building blocks of this myth.

1: Jung did not discover the Intuitive Function. That was Maria Moltzer.

Jung originally operated with only two types, EF and IT. However, in 1916, five years prior to the publication of Psychological Types, Jung’s assistant Maria Moltzer gave a talk before the Jungian community in which she said:

“In my opinion a misuse has been made … of types. … People [are] forced into one of the two categories [EF or IT] according to this very superficial diagnosis.”

Protesting Jung’s use of only two types, Moltzer therefore added a third, namely the Intuitive type. As is known, in Jung’s final definition of Intuition, he describes Intuition as “perception via the unconscious.” It is thus striking to see that already in 1916, Moltzer describes Intuition as a function that “registers the impressions received in the unconscious.” Likewise, foreshadowing van der Hoop’s later characterization of Intuition as a “primitive” function, Moltzer had also said in 1916 that Intuition was an evolutionarily older mode of adaptation than Thinking and Feeling.

Prior to Moltzer’s presentation, Jung had thought that Intuition was not a separate function, but a psychic impulse that operated equally in all types. It was Moltzer’s presentation that caused him to revise his thinking. Indeed, Jung credits her for as much in Psychological Types §773. But as researchers have pointed out, this one solitary reference in all of Jung’s works seems to be shortchanging the deep-keeled influence that Moltzer had on him, especially when we consider that she was one of his closest associates at the time.

Something was indeed amiss, and by 1918 Moltzer had resigned and left Jungian circles entirely. Her reasons for doing so are lost to history, but two possibilities stand out: One is that Moltzer’s intellectual contributions were taken for granted by Jung. For her own part, Moltzer seems to say as much in a letter:

“I could not live any longer in that atmosphere. I am glad I [resigned]. … It seems that I openly don’t get the recognition or the appreciation for what I do for the development of the whole analytic movement.”

Another salient possibility for Moltzer’s resignation may have been that she was one of Jung’s many lovers within the movement. While there is no “smoking gun” that definitively confirms the existence of such an affair, there is nevertheless a wide-ranging paper trail of insinuations in the personal letters of both Jung, Moltzer, and other members of the Jungian circle. Likewise, we also know that Moltzer thought of herself as “allowing” Jung to live a pleasurable polygamous lifestyle, again pointing strongly to the possibility of a love affair. While not all of Jung’s extramarital love affairs ended badly, many of them did. If that was the case here, it is possible that Moltzer resigned from the Jungian circle in order to deal with the hurt from a distance. [Update August 2014: Since we wrote this article, we found a source where Jung’s associate Jolande Jacobi confirms that Jung and Moltzer had an affair.]

Of Moltzer’s personal type, we know that Hans Schmid-Guisan, who collaborated with Jung on early type theory, thought she was an extrovert.

Read more about this: Sonu Shamdasani: Jung and the Making of Modern Psychology, Cambridge University Press 2003 ed. p. 70 ff. // Richard Noll: The Aryan Christ, Random House 1997 ed. p. 190 ff.

2: Jung originally thought all Feeling was extroverted. Fi was discovered by Jung’s friend and colleague, Hans Schmid-Guisan.

In 1915, while Jung was still operating with only two types, his collaborator on the type problem, Hans Schmid-Guisan, suggested that there existed a kind of Introverted Feeling (Fi):

“[It is an introverted process] that is not an act of thinking, not an intellectual process, but exclusively a matter of feeling. … [It] feels in an abstract way [and] will not demand certain feelings from [external reality] but merely seeks to realize [its] own feelings as deeply as possible.”

Like Moltzer’s prefiguring of Intuition, Schmid-Guisan’s anticipation of Fi is eerily accurate. As both Jung and his student Marie-Louise von Franz would later say, Fi does not need to acquaint the outer world with its feelings. The Fi type can be quite content to experience his own feeling life on the inside, in a parallel world where the other person never knows that he or she is the object of such strong feeling valuations inside the Fi type. It would take Jung and von Franz several years to understand this insight. But already in 1915, Schmid-Guisan would say of the Introverted Feeling function that there were “cases where this process went ahead pretty far without the [object of the Fi type’s valuations] knowing about it.”

Of Schmid-Guisan’s personal type, we know that he and Jung considered him to be an extrovert (EF) type, while the later Jungian analyst and M.D. John Beebe considered Schmid-Guisan an ENFP.

Read more about this: Jung & Schmid-Guisan: The Question of Psychological Types, Princeton University Press 2013 ed., p. 92 ff. // C.G. Jung: Psychological Types, Harcourt & Brace 1923 ed., p. 492 // Von Franz & Hillman: Lectures on Jung’s Typology Spring 1971 ed., p. 39

3: Jung did not write Psychological Types on his own.

As we said in the beginning of this article, Jung is often depicted as seemingly spinning Psychological Types out of his own brain with little outside help. As we have seen, Jung was stingy with crediting others for collaborating on his type theory, and in certain interviews at a later date he would also describe the origin of his type theory in terms that would indicate that he was the sole mind behind it:

“I saw first the introverted and extraverted attitudes, then the functional aspects, then which of the four functions is predominant. Now mind you, these four functions were not a scheme I had invented and applied to psychology. On the contrary, it took me quite a long time to discover that there is another type than the thinking type, as I thought my type to be. … There are, for instance, feeling types. And after a while I discovered that there are intuitive types. They gave me much trouble. It took me over a year to become clearer about the existence of intuitive types.”

Notice here how Jung is speaking only of himself as having discovered the Intuitive type. There is no mention of Moltzer. But as we have seen, it was not Jung who discovered the Intuitive type, but Moltzer. Nor did Jung discover the Fi type. That was Hans Schmid-Guisan. What about the Sensation type, then? Jung goes on:

“And the last, and the most unexpected, was the sensation type. And only later I saw that these are naturally the four aspects of conscious orientation. … [These are] the four functions. … I haven’t found more. … So through the study of all sorts of human types, I came to the conclusion [that there were four functions].”

Again the phrasings suggest that Jung was alone in making these discoveries. But in fact, Jung did not discover the Sensation function either. And he was far from alone in writing Psychological Types.

First, the Sensation types were introduced to Jung by his fellow analyst (and extramarital lover) Toni Wolff . However, as opposed to Moltzer, who is at least credited once in Psychological Types, Wolff isn’t mentioned in the book at all. And unlike Moltzer, who gave her presentation on the Intuitive type publicly, Wolff is thought to have introduced the Sensation type to Jung in private, as well as a reworked version of Moltzer’s Intuitive type that would fit better into Jung’s overall system of types.

Because there is no written record to document Wolff’s influence on Jung, it is hard to pin down the exact nature of Wolff’s contribution. But Jung researchers as diverse as Sonu Shamdasani, Richard Noll, Deirdre Bair, and John Beebe, as well as Jung’s own personal secretary during the period, all agree that Wolff deserves crucial credit for introducing the Sensation type and the reworked Intuitive type to Jung.

Even quite apart from the contributions of Maria Moltzer, Hans Schmid-Guisan, and Toni Wolff, Jung was far from alone in crafting the rest of Psychological Types. Instead, modern researchers have documented how Jung had a steady committee of about half a dozen people who helped him develop the ideas of the book and who seem to have had an internal mailing list, dedicated solely to developing ideas on types. Likewise, the wider Jungian circle would also meet to discuss type theory, and draft sections of Psychological Types would be read aloud and discussed at such gatherings. Far from being a work of individual genius, then, Psychological Types is a collaborative research effort.

Read more about this: C.G. Jung Speaking, Princeton University Press 1977 ed. p. 341 ff. // Deirdre Bair: Jung – A Biography, Paw Prints 2008 ed. p. 742n // Sonu Shamdasani: Jung and the Making of Modern Psychology, Cambridge University Press 2003 ed. p. 68 ff.

4: Some of Jung’s supernatural and religious visions can actually be tested.

From his earliest childhood years, Jung had an extremely vivid and active imagination. In the early part of his career, he tried to play the role of empirical scientist, but as the years progressed, Jung became increasingly more mystical and religious. After 1914, Jung often claimed that he received his insights in divine visions and through omens and dreams. There are even some cryptical remarks on the connection between his visions and his type theory, as featured in Notes on the Seminar Given in 1925, but the precise meaning of these references have not been fully understood by researchers.

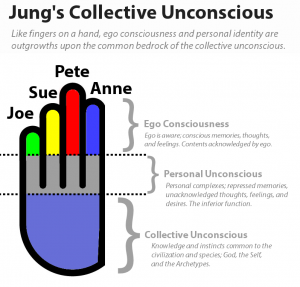

As Jung aged, he often claimed (in the style of Plato) that inner visions were more real than outside existence. As previously explored on the site, he also claimed that he and others could acquire knowledge of the past through his concept of the Collective Unconscious. Given the nature of these claims, it is very hard to test their validity. How does one test the truth value of mystical and subjective fantasies, or of almost metaphysical concepts like the Collective Unconscious?

Testing the truth-value of Jung’s fantasies and concepts is commonly thought to be practically impossible and thus it is left to a matter of personal faith. Thus Jungians tend to believe in them, while non-Jungians do not. But there is in fact one way to test at least one of Jung’s visions.

One vision that Jung claims to have had and which was “real” was his acquaintance with the mysteries of the Roman cult of Mithras (1st to 4th centuries CE). In one of his visions, Jung believed that he had been initiated into the ancient mysteries of the Mithras cult. As he said:

“One gets a peculiar feeling from being put through such an initiation. … In this deification mystery you make yourself into the vessel.”

If Jung’s visions were real (and not just imagined), we would expect that his conception of the Mithras cult should be true independently of the academic process that takes place as more and more of the archeological record is reviewed and discussed by scholars. Here the convenient circumstance for our purposes is that historical knowledge keeps evolving as more evidence comes to light and theories are refined and criticized. In other words, today’s historical scholarship on the Mithras cult is not at all what is was in the 1910s where Jung was reading about it. So if Jung’s vision was “real,” his account of the Mithras cult should be closer to the accounts that we have today than to the preliminary accounts of the 1910s that were the ones that Jung could have gleaned from books.

But it isn’t. In fact, Jung’s ideas about the Mithras cult are dead ringers for the conceptions of Mithras that were in vogue in the Europe of Jung’s own time. For example, in the 1910s, Mithras was widely regarded as being an ancient Iranian solar deity, appropriated by the Romans for their own religious uses. But modern scholarship has largely dismissed this view on the basis of evidence suggesting that the Mithras cult was constructed within the Roman Empire to begin with. Likewise, far from being an Apollonian solar deity, modern scholars regard Mithras as a kosmokrator – literally a “ruler of the universe” – which is to say that he was conceived as something far more powerful than a deity akin to Apollo.

But it isn’t. In fact, Jung’s ideas about the Mithras cult are dead ringers for the conceptions of Mithras that were in vogue in the Europe of Jung’s own time. For example, in the 1910s, Mithras was widely regarded as being an ancient Iranian solar deity, appropriated by the Romans for their own religious uses. But modern scholarship has largely dismissed this view on the basis of evidence suggesting that the Mithras cult was constructed within the Roman Empire to begin with. Likewise, far from being an Apollonian solar deity, modern scholars regard Mithras as a kosmokrator – literally a “ruler of the universe” – which is to say that he was conceived as something far more powerful than a deity akin to Apollo.

Of course it is possible that the historians and archeologists of the 1910s (i.e. the scholars that Jung had read) were right about everything and that the scholarship of the last 100 years has only managed to present mistakes and distortions. But on the whole of it, the compliance between Jung’s visions and the historical scholarship of his time suggests that Jung was not able to attain independent knowledge through visions or the Collective Unconscious, but that he merely had a gift for personalizing and reshaping knowledge that he already had, so that it would fit into a grand synthesis.

Read more about this: Richard Noll: The Aryan Christ, Random House 1997 ed. p. 122 ff. // C.G. Jung: Notes on the Seminar Given in 1925, Princeton University Press 1989 p. 96-98