By Ryan Smith and Sigurd Arild

The current state of Jungian typology is such that Jungian concepts that do not directly relate to type are sometimes thrown around to spice up people’s experience and presentation of typology. In particular, Jung’s idea of archetypes is often mentioned in order to complement people’s understanding of type. However, the general understanding of these lines of thought appears to be poor and/or wrong.

For example, Jungian functions are sometimes referred to as archetypes, just as four-letter type codes are sometimes referred to as archetypes. These are both erroneous views.

For example, Jungian functions are sometimes referred to as archetypes, just as four-letter type codes are sometimes referred to as archetypes. These are both erroneous views.

When Jung spoke of archetypes he meant something like the fact that when the Greek Prometheus resembles the Nordic Loki (and when they both resemble Bugs Bunny or Q from Star Trek) that is because they all embody a Trickster archetype. Archetypical themes, in short, are far more nebulous and abstract than Jung’s normal types.

Like Plato, Jung started his career studying the empirical realm in earnest (such as his studies in word association and schizophrenia) but then gravitated towards increasingly mystical ideas. Also like Plato, Jung’s career can be divided into three parts, namely an early, middle, and late period.

Jung’s theory of normal types belongs to Jung’s middle period when he had started mixing elements of mysticism into his empirical findings, but when he was still concerned with making an objectively tenable case.[1] But his theory of the archetypes belongs to the late period, where Jung can no longer be considered an empirical thinker.[2]

Here’s a rundown on Jung’s basic ideas regarding the archetypes.

Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious

Why did primitive humans go to such lengths to interpret the rising of the sun and the equinox? Why did prehistoric Britons labor for hundreds of years to align Stonehenge with the stars? In Jung’s view it was because man is not merely the rational animal that modern society has made him out to be. Man has always needed ‘exterior’ things such as shelter, sex, food, and possessions. But for as long as we have been homo sapiens, we have also needed ‘inner’ things like meaning, art, religion, and mythology.

In Jung’s view we have now shifted society so gravely in favor of our external needs that we have totally forgotten about the inner needs. According to Jung, this makes our normal consciousness very narrow and short-sighted. It literally makes us forget half of ourselves and we become ill as a result.

What we must do, says Jung, is to try and re-establish our connection to the inner world of meaning that our forebears had. Instead of living in a wholly rational world of diet plans and tax returns we should try to rekindle archetypical and mythological themes in our own lives. Loki and Prometheus may not be worshiped in our communities, but the Trickster archetype is still engraved in the collective unconscious as a symbol of meaning that, if ignited within us, can steer us to greater deeds in life.

What we must do, says Jung, is to try and re-establish our connection to the inner world of meaning that our forebears had. Instead of living in a wholly rational world of diet plans and tax returns we should try to rekindle archetypical and mythological themes in our own lives. Loki and Prometheus may not be worshiped in our communities, but the Trickster archetype is still engraved in the collective unconscious as a symbol of meaning that, if ignited within us, can steer us to greater deeds in life.

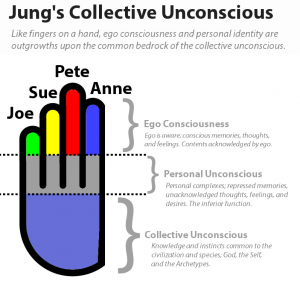

According to Jung, the Trickster archetype is just one such archetype, along with the Mother, the Shadow, the Anima/Animus, God, and the Self. The Self is the most important of these archetypes, as it is the focal point through which the individual (existing in flesh and blood in the empirical world) interacts with the archetypes (that are nested in the meta-empirical realm of the collective unconscious).

According to Jung, it is the Self that unites the conscious and personal unconscious with their archetypes of the collective unconscious. And it is when the archetypes are manifested in the world with the help of the Self that the individual is able to express the collective wisdom of the species that is beyond their own existence in, and experience of, the world.

Indeed, according to Jung, it is only the person who has successfully manifested archetypes in the world who can be considered a full and whole individual. In Jung’s view, both our everyday consciousness as well as our conception of ourselves is very limited when viewed against the background of the collective unconscious and the archetypes, and in the later part of his career, Jung appears to have lost interest in normal types, preferring instead to concentrate all his work on the archetypes.[3]

Jung’s Arguments for the Archetypes

As we have said, Jung’s theory of the archetypes cannot be considered to have much scientific support. However, Jung himself believed that the archetypes existed literally, and he advanced a number of arguments for why we should believe in them. So let’s look at three of Jung’s arguments for the existence of archetypes and the collective unconscious.

First argument: When Jung presented his idea of the archetypes, it was immediately considered mystical and unscientific by his colleagues. But to defend himself, Jung pointed out how Freud had found a new, seemingly mysterious, and unscientific notion in the concept of the personal unconscious and that this view was now considered valid.[4] However, this argument does not do much to prove Jung’s idea. At best, it reads more like a deflection than an actual argument.

First argument: When Jung presented his idea of the archetypes, it was immediately considered mystical and unscientific by his colleagues. But to defend himself, Jung pointed out how Freud had found a new, seemingly mysterious, and unscientific notion in the concept of the personal unconscious and that this view was now considered valid.[4] However, this argument does not do much to prove Jung’s idea. At best, it reads more like a deflection than an actual argument.

Second argument: Another argument that Jung advanced as proof of the collective unconscious is that people are sometimes able to express themes and thoughts that they have seemingly never experienced themselves. In Jung’s own experience, a patient he was treating for schizophrenia would suddenly be able to tell him the same things that Jung had previously read in some ancient Egyptian papyrus scrolls.[5] Since there was no way the patient could have known the contents of the scrolls, Jung then concluded that the contents must have come to the patient through universal thought-forms or mental images, that is to say, through archetypes that well up through the collective unconscious.

In analyzing this second argument, we must first note that people generally have a habit of coming upon stories that prove whatever thesis they want to advance. Palm readers will tell you the most amazing stories of what hand reading can do, astrologers pay due tribute to horoscopes, and people who think they can determine Jungian type by “face reading” will tell you about the “hard evidence” that it “really works.” [In reality, it has never been proven to work.]

Because we know that people fall in love with their own theories, we no longer accept their theories based on assurances alone. For stories such as the schizophrenic who rambles off ancient Egyptian formulae to count as evidence, and not as mere stories, they must be demonstrated to occur in controlled experiments.

Another line of inquiry regarding Jung’s second argument is this: Suppose the schizophrenic suddenly knew something which there was no normal way that he could possibly have known. That still doesn’t prove anything about the existence of the collective unconscious. That archetypes influenced the person through the collective unconscious is a possibility, but there is nothing in the occurrence to necessitate, or even point to, the existence of archetypes. So even granting that the incident with the schizophrenic patient is true, that still doesn’t prove Jung’s theory as much as it simply points to a hole in our normal understanding of the world.

As the Jung biographer Frank McLynn has said, Jung “seemed unable or unwilling to understand that because a set of data is compatible with hypothesis X, it does not thereby prove X. The same set of data could just as well [fit] dozens of other hypotheses.”[6]

Third argument: The third of Jung’s arguments for the existence of the archetypes is that when people experience archetypes, their behavior does not conform to the everyday expectations of society. According to Jung, since these experiences apparently cause individuals to break out of their normal personalities, this means that the individual is influenced by something outside himself.

This argument has a logical structure but when examined, it will be seen that the argument is actually unfalsifiable (meaning that it cannot be proved or disproved). It may be that the ultimate cause of psychosis, strokes of genius, and temporary insanity is really archetypes, but again, since we cannot prove or disprove them, the ultimate cause of these phenomena may just as well be something different.

Thus all of Jung’s arguments for the existence of archetypes are deeply unsatisfying when examined with a critical mind. Furthermore, on examining Jung’s descriptions of the archetypes and how they are supposed to function, we find that he had no clear or consistent definition of the concept: In some places, the archetypes are treated as Platonic forms, in others as Kantian-Schopenhauerian things-in-themselves, and in other places still as akin to biological instincts, like the migrating instinct in birds.[7]

However, the people who use these concepts tend to just assume that they are true. In this, they follow Jung who, according to reports, would simply sit at medical conferences and talk at (not to) other psychiatrists as if his theory of the archetypes had already been proven and there were nothing to doubt or discuss.[8] Indeed, it seems that whether these ideas are true or not is not of foremost importance to the people who are using them. Their real allure is the perspectives that assuming them to be true can engender.

Consequences of the Collective Unconscious

Why is psychology so young? According to Jung, the various religions and mythologies that all cultures have previously followed have kept us nourished in regards to our ‘inner’ needs for meaning, art, and understanding. In Jung’s view, it was the Protestant reformation of Christianity that cleaned out the unconscious and irrational parts of the mind, leaving us rationally strengthened but spiritually and aesthetically amputated.

The proof, Jung believed, can be seen in the modern attraction to fantasy universes like Lord of the Rings: These fantasy worlds manifest archetypes just like ancient mythologies did. However, because we know they are fantasies, they are not psychologically conducive to ‘inner’ needs the way the old mythologies were.

In Jung’s view, it is interaction with archetypical themes that sets us on the path to what he called individuation – a form of self-development that occurs when one struggles to integrate all opposites within oneself. Individuation was in itself the point of much of Psychological Types, and several chapters are clearly written in order to illustrate how a strongly expressed type also implies a need to find one’s way back to integration and wholeness (e.g. if you are an Ne type, your individuation process will entail that you should at some point in your life seek to activate an archetypical theme that is stable, steady and static, to integrate your Si).

In this way, Jung’s typology was not intended as a descriptive, psychometric typology, but as a normative guide to “becoming whole.” Nevertheless, all other writers (including von Franz and van der Hoop) have more or less left this normative aspect of Jungian typology behind.[9]

Today, Jungian typology and its derivatives are often marketed as helping you “find your strengths” or “find the hero in you,” but Jung would no doubt have recoiled from such wanton capitalization on the typical strength of one’s two uppermost functions. As he saw it, it is the serious and lasting responsibility of the individual to take responsibility for his own self-development and integrative wholeness.

At the time when he wrote Psychological Types, Jung took individuation to mean the integration of one’s two lowermost functions and opposite orientations.[10] But as he discovered the archetypes and the collective unconscious, he came to see individuation as concurrence with the collective unconscious and he left the idea of “normal types” behind.

Once individuation is achieved, you are no longer a slave to your cognitive functions (middle period Jung) or to the social and rational expectations that are pressed upon your person by society (late period Jung). Like the sphere of Parmenides, you are well-rounded, whole, complete and unshakable, and not lacking a single thing.

Like Plato, Jung stressed that individuation is not a rational process. It is not that he is against reason, he merely thinks that the true realization of what one is goes beyond normal thinking. Like Plato’s Symposium §210a-212c, where reason is the fifth step on the seven-step ladder towards the ultimate realization, there are higher modes of thought that are not normally known to us in our everyday lives.

Our Own View

The Jungian notion of archetypes and the collective unconscious is essentially metaphysical. Unlike Jung’s notion of psychological types, which has an “acceptable” degree of scientific support, there is no scientific or empirical evidence to support the notion of archetypes and the collective unconscious in the way Jung conceived these ideas. That doesn’t mean these ideas are wrong, but nor does it mean that these ideas can be taken for granted. Like belief in a Kantian noumenon, whether one believes in it or not, one should always try to separate one’s metaphysics from one’s empirical findings.

***

Jung’s Concept of Archetypes © 2014 Ryan Smith, Sigurd Arild, and CelebrityTypes International.

With art by Georgios Magkakis and research by C.G. Jung and Tom Butler Bowdon.

NOTES

[1] An example of a mystical element in Jung’s theory of the types is Jung’s claim that Ni types are supposedly capable of seeing into the Kantian noumenon, as found in Psychological Types §659. An interesting aside here is that though Kant would probably never accept that anyone (except God) would be able to see the noumenon as noumenon, and Jung appears to have misunderstood Kant, Jung was right in the sense that Ni types often think they can see the entirety of reality and that there are no ontological or structural impediments to their perception. In this way, though Jung is wrong in his exposition of Kant, his phrasing is still instructive.

[2] Though Jung always claimed that he was an empiricist, what he seems to have meant was that he approached his clinical experience with patients with an open mind. However, with regards to the scientific meaning of the word “empiricism,” this type of evidence is worth nil.

[3] Van der Hoop: Conscious Orientation, Routledge 1999 ed. pp. viii-ix

[4] Although as the psychologist H.J. Eysenck has documented, the idea of the personal unconscious was not so much invented by Freud as it was operationalized by him. In Eysenck’s view, hundreds of thinkers had ideas that were strikingly similar to the Freudian unconscious, going all the way back to Plotinus and the Neo-Platonists who were convinced that feelings and thoughts could be present in the individual without any conscious awareness of them. On the topic of Jung’s archetypes and collective unconscious, Eysenck (who did accept Jung’s main typology) called Jung’s later concepts “vague and essentially untestable.” See: H.J. Eysenck: Genius – the Natural History of Creativity, Cambridge University Press 1995 ed. p. 179

[5] Jung: C.G. Jung Speaking, Princeton University Press 1977 ed. p. 44

[6] McLynn: Carl Gustav Jung – A Biography, Black Swan 1997 ed. p. 312

[7] McLynn: Carl Gustav Jung – A Biography, Black Swan 1997 ed. pp. 312-313

[8] Stern: C.G. Jung – The Haunted Prophet, George Braziller 1976 ed. pp. 223-224

[9] An exception can be found in James Graham Johnston’s Jung’s Compass of Psychological Types (albeit the book does not commit itself to a purely normative approach and purpose. See our review here).

[10] Though it seems that people are always some ‘type’ and that they almost never change that ‘type.’ So either Jung’s idea here was wrong, or no one has actually managed to become individuated. A third option is that individuation is gradual, and thus that many have achieved some measure of individuation but no one has achieved full individuation.