By Ryan Smith

“[I have meditated] on Plato’s secrecy and sphinx-like nature.”

– Friedrich Nietzsche: Beyond Good and Evil §28

As far as we know, Plato never told us anything directly. Rather he wrote a series of dialogues from which a certain philosophy and temperament can be noticed by the person who endeavors to read them all. In addition to that we have some letters that were supposedly written by Plato (which he seems to have wanted the recipients to burn) and a ragbag of contemporary testimonies about him (not all of which are reliable and none of which were authorized by him).

It would seem, then, that Plato didn’t want us to be able to connect his opinions with him as a human being. Through the dialogues he wanted to provoke us to start thinking along the lines of his own teaching, but at the same time he avoids putting the matter of his opinions to us directly, so that Plato the man remains entirely above the fray of whether we will accept the ideas expressed in the dialogues or not. The intent seems to have been that if we end up agreeing with Plato through reading his dialogues, it would not seem as if we learned these thoughts from Plato, a mere man, but rather that we have seen for ourselves how the Platonic ideas were evidently true in themselves.

Since Plato consistently maintained a “secrecy and sphinx-like nature” throughout his 80-some years of life, it is all the more fascinating to learn that he had an Unwritten Doctrine, in which he supposedly revealed his highest teachings. What was the nature and content of this Unwritten Doctrine? Scholars have been trying to reconstruct its content for some 2300 years, using various approaches to try and uncover its meaning. In this article I shall try and do the same while using a few pointers from Jungian typology to fill in the blanks.

Definition: The Theory of Forms

Before we proceed, let us quickly recap the Theory of Forms. Readers already familiar with this theory can skip to the next heading.

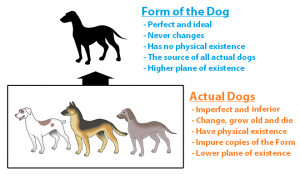

Plato’s Theory of Forms says that every object in this world is but a pale shadow of the ideal Form of the object, which exists only as thought and has no material existence. For example, you may have an actual, physical dog as your pet and your best friend may have another actual, physical dog as his pet. But the way Plato sees it, none of these dogs are actually as real as the ideal Form of the Dog, which exists only as an idea. That ideal dog is perfect, whereas physical dogs are imperfect. Physical dogs grow old and die, but the ideal dog is eternal and unchanging and it cannot be altered by anything that takes place on the physical level.

Plato’s Theory of Forms says that every object in this world is but a pale shadow of the ideal Form of the object, which exists only as thought and has no material existence. For example, you may have an actual, physical dog as your pet and your best friend may have another actual, physical dog as his pet. But the way Plato sees it, none of these dogs are actually as real as the ideal Form of the Dog, which exists only as an idea. That ideal dog is perfect, whereas physical dogs are imperfect. Physical dogs grow old and die, but the ideal dog is eternal and unchanging and it cannot be altered by anything that takes place on the physical level.

Furthermore, the Forms belong to a higher plane of existence than physical objects. As said, the ideal Form of the Dog is more real than actual, physical dogs. Likewise, even if there were no physical dogs, the Form of the Dog would still exist, as what goes on in the realm of Forms is wholly separated from the realm of matter and physical experience.

Here is Plato explaining his Theory of the Forms, only here he is describing the Form of Beauty, instead of the Form of the Dog:

“The culmination of beauty … [is to] catch sight of something of unbelievable beauty … which gives meaning to all previous encounters [with beauty]. … [It is] something eternal; it doesn’t come-to-be or cease-to-be, and it doesn’t increase or diminish. … It [has] no physical place … [but is] in itself and by itself, constant and eternal … and every beautiful physical object somehow partakes in it, but in such a way that their coming-to-be and ceasing-to-be don’t increase or diminish it at all, and it remains entirely unaffected. … [It is] beauty itself, in its perfect, immaculate purity – not beauty tainted by human flesh and coloring and all that mortal rubbish, but absolute beauty, divine and constant.”

– Plato: Symposium §211a-e

The Three Periods of Plato’s Career

Plato’s career may traditionally be divided into three parts:

EARLY PERIOD

Plato witnesses Socrates’ execution. Plato writes philosophy reconstructing Socrates’ opinions. (Plato is one follower of Socrates among several). Plato’s philosophical method in this period consists of testing ideas through a series of questions and answers in the style that Socrates supposedly used. The method breaks down conventional certainties (“what is justice?”; what is good?”; “what is piety?”) without putting anything in place of the newly created vacuum. In the early period, the only thing the wise man knows is that he knows nothing.

MIDDLE PERIOD

Plato founds the academy, writes philosophy and develops the Theory of Forms. At his academy, Plato teaches his Theory of Forms to the brightest minds in Athens. His teaching is a success and he attracts attention far and wide. Plato’s philosophical method in this period is a mixture of the Socratic-style questions and answers that we know from the early period and new elements of an edifying dialectic. The middle period therefore also sees Plato breaking down certainties in the early Socratic style (“what is good?) but now he re-furnishes the vacuum by offering a new understanding (“good is that which springs from the Form of Good”).

LATE PERIOD

Several of Plato’s brightest students leave the academy over philosophical disagreements with Plato. The Theory of Forms is no longer as admired and prestigious as it once was. Plato writes philosophy exploring the deeper relationship between the Theory of Forms and the ultimate nature of the universe (“what is the nature of Being?”; “what is the nature of nothing?”).

In his late period, Plato also conducts investigations into the relationship between the Forms and definitions (“when is a politician a politician?”; “if a teacher charges tuition, is he still a teacher, or is he now a merchant?”). Plato’s philosophical method does not make use of Socratic-style questions and answers anymore, but now follows a method that collects “names and kinds” and then deductively analyzes and divides kinds.

(For example, if we ask: “What is a politician?” we start by collecting similar “names and kinds” such as ‘king’, ‘slave master’, and ‘ox-herder’ who all have the power to rule others the way a politician does. Then we divide these names and kinds according to deduction: The ox-herder does not rule humans, and the slave master does not possess knowledge of statecraft. Thus the king is the kind that is closest to the politician.)

What Happened During Plato’s Late Period?

What is puzzling to scholars is that there are several places in Plato’s late writings where Plato attacks his beloved Theory of Forms and seemingly does not defend it. The attack is typically left to germinate with the reader without an adequate line of defense being provided by the dialogue itself. Did Plato then intend for the reader to not believe in his Theory of Forms? Is this evidence that Plato gave up the centerpiece of his own philosophy, the Theory of Forms, during his late period? And if he did, why didn’t he say so more fervently?

Scholars are divided on the topic:

Unitarians think that Plato’s philosophical theory was essentially the same from his youth to his death. The questions raised throughout the early, middle, and late periods can all been seen as continuous. We are dealing merely with the development and refinement of the same basic theory, namely the Theory of Forms, and Plato never doubted or revised his Theory of Forms.

Revisionists believe that Plato ran into a crisis in his late period and that he probably revised his Theory of Forms to be less contentious. An oft-cited view amongst the Revisionists is that Plato made his Theory of Forms more Aristotelian because Aristotle’s school was gaining in prominence and because it was easier to relate Aristotle’s thinking to experiment and concrete observation.

Now, as the scholar John Pebble has pointed out, each of these camps has a strong point, and each strong point is at the same time also a chink in the other party’s theory:

The Revisionists play the trump card that the writings from Plato’s late period appear more searching and less certain than the writings from his middle period. If Plato did not experience any kind of intellectual crisis, why does he appear to grow less (as opposed to more) certain of his own views? Moreover, in his late dialogues, Plato is often seen hammering away at his own Theory of Forms without attempting to actually defend his own theory. If Plato was still a vehement believer in his Theory of Forms, why did he not try to defend it more thoroughly?

Furthermore, in Plato’s middle period, Socrates had been the mouthpiece for Plato’s Theory of Forms. But in Plato’s late period, Socrates is demoted and it is now Parmenides (who did not believe in the Forms) who is seen as the new metaphysical master. Does that not indicate that Plato had a diminishing commitment to the Theory of Forms?

Perhaps it does. But be that as it may, The Unitarians also have a strong point: Even though Plato seems rather impassive with regards to defending the Forms in the late writings, and even though Parmenides replaces Socrates in the role of metaphysical master, these are only circumstantial types of evidence. There is no actual evidence that Plato ever revised his core theory.

One instance of this argument runs like this: We know that Aristotle compiled most of the philosophical arguments available to him, but he never mentioned any “revised” views of Plato. Now some Revisionists try to get around this weakness in their theory by claiming that the reason there is no mention of any revised views of Plato’s in Aristotle’s compilations is because Plato revised his theory to be completely consistent with Aristotle’s. But there are a number of problems with this defense:

- Unitarians say that Revisionists shouldn’t base their arguments on circumstantial evidence, but that they need direct and actual proof. So obviously Revisionists cannot purport to answer this challenge by coming up with new speculations whose standards of proof are even lower than those of the original speculations they sought to justify.

- If Plato revised his Theory of Forms to be essentially the same as Aristotle’s, and the two were locked in a bitter rivalry over academic prestige, why didn’t either of them (or their followers) accuse the other of stealing ideas?

- If Plato is INFJ and Aristotle ENTJ, it would be very unlikely (though not impossible) that Plato should give up his transcendental theory, which was derived from inner ideas, for an empirical theory that was derived from external data, given that Ti feeds off the inner ideas and Te feeds off the external data.

- Moreover, it would also be exceedingly strange for the world-denying Plato to accept sense-data as an independent and legitimate arbiter of reality, especially given his historical time and place.[1] (Note that I am not talking about the unconscious longing to reunite with the inferior function here.)[2]

Thus both Revisionists and Unitarians have a strong point in favor of their own theory which they can at the same time use as a chokehold on the other to keep it from gaining ascendency.

The matter, then, is at an impasse and has been for years. None of the two lines of thought can adequately explain what happened in Plato’s late period without disregarding a wealth of central facts.

This still leaves us with the basic question: What happened during Plato’s late period?

One thing we know for a fact is that the Third Man happened.

Definition: The Third Man Argument

Before we proceed, let us quickly recap the Third Man Argument. Readers already familiar with this argument can skip to the next heading.

The Third Man Argument was a criticism leveled at Plato’s Theory of Forms. It is sometimes attributed to Aristotle, but it need not have been coined by him. It could have originated with another of Plato’s students, or even with Plato himself.

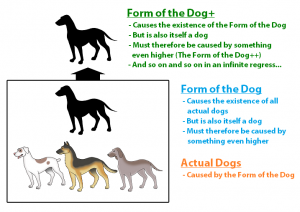

As we recall, Plato had said that every class of objects was derived from the ideal and perfect form above it. For example, all dogs that exist in this world are imperfect copies of the ideal Form of the Dog.

The Third Man Argument asks: “Isn’t the Form of the Dog itself a dog?” If it is, then the Theory of Forms would imply that the Form of the Dog was also caused by caused by a Form.

This third Form could then be called the “Form of the Dog+.” But since that Form is also a dog we would need to posit the existence of a “Form of the Dog++” and so on and so on, causing an infinite regress of Forms and rendering the theory incomprehensible or meaningless.

This third Form could then be called the “Form of the Dog+.” But since that Form is also a dog we would need to posit the existence of a “Form of the Dog++” and so on and so on, causing an infinite regress of Forms and rendering the theory incomprehensible or meaningless.

Whether this argument is valid or not has been violently debated in both ancient and modern times. However, no matter whether it is valid or not, the argument is intelligently constructed.

Towards the Unwritten Doctrine

During the latter part of his career, the Third Man Argument “happened” to Plato. He even refers to the Third Man Argument as something that causes most people to give up belief in his Theory of Forms when they hear it (Parmenides §135a). However, Plato never says that the Third Man Argument is valid; he only says that it has a cogent effect on the people who hear it.

Modern scholars tend to assume that Plato either abandoned his Theory of Forms (Revisionists) or that he was more or less unperturbed by the criticism he received and carried on in his own way (Unitarians). However, as we have seen, neither of these theories are able to explain what happened during Plato’s late period.

In our next installment of this essay we shall attempt to discover what happened during the late part of Plato’s career, as well as to recover the contents of his Unwritten Doctrine.

***

Plato’s Unwritten Doctrine and Jung’s Typology © Ryan Smith and CelebrityTypes International 2014.

Images in the article commissioned for this publication from artist Georgios Magkakis.

NOTES ON PLATO’S INFERIOR SE

[1] By ”historical time and place”, I actually allude to two seemingly opposite arguments. One is that in Plato’s own time there was not yet the established supremacy of the experimental method that we have today and a long and successful history of science behind us to suggest that empirical evidence cannot be downplayed or ignored. In other words, the history of science and the scientific method carries its own recommendation to all observers in the modern day and age, regardless of temperament. But in Plato’s time, the historical record on the success (or lack thereof) of the experimental method in science was extremely meager, and therefore reasonable people could disagree to a greater extent. In other words, type preferences would have a greater bearing on the philosophical outlook of a man in the intellectual atmosphere of Ancient Greece (where more epistemological balls were still up in the air) than it will today (where few educated people would venture to deny the primacy of the experimental method in science). The other argument that I should like to allude to is that once we view Plato in relation to his historical time and context, we will see that Plato’s world-denying, sensory asceticism is actually far more radical, idiosyncratic, and self-caused than is usually supposed to be the case. As the scholar John D. Turner has pointed out, almost everything about Greek philosophy and religion up to the time of Plato had consisted in accepting the world through “the ordinary human experience of corporeality.” Plato then flips the notion of what is real on its head: What was formerly real (concrete, personal experience) is now deemed to be unreal illusions that cloud mortal judgments. What is really real, according to Plato, is the incorporeal, immaterial, and unchanging Forms that exist in a realm of Being that stands apart from the material, sensory experience of the cosmos. (See: Turner: Sethian Gnosticism and the Platonic Tradition, Les Presses De L’Universite Laval Quebec 2006 ed. p. 448 and also n2.) So to sum up: (A) There was no hegemonic pressure for reasonable men to accept experimental science in Plato’s day. This observation counts against the Revisionist conjecture that Plato revised his Theory of Forms to be in complete agreement with Aristotle’s more experimental approach to the Forms. (B) Plato’s denying stance towards the physical and sensible world was even more radical than is usually assumed. Once we place Plato in his historical context, we see that Plato’s world-denying stance had no intellectual, cultural, or social predecessor and can only be explained by Plato’s personal volition. All the more reason to doubt, then, the Revisionist conjecture that Plato adopted Aristotelian empiricism in the face of the criticisms that his Theory of Forms met with.

[2] For Plato to have accepted the Aristotelian approach to sensation would not have constituted a return of the repressed in the manner of the repressed impulses and cognitions returning to consciousness in unconscious and uncontrollable form. What Aristotle advocated was a relaxed and pragmatic attitude to Sensation, allowing us to obtain observational and experiential data about the world, but letting the ordering of that data be the ultimate arbiter of what is real. However, the inferior Se of INJs is not relaxed and pragmatic, but always extremely intense, and has an ‘all or nothing’ manner to it. (See: Von Franz, in von Franz & Hillman: Lectures on Jung’s Typology, Spring Publications 1984 p. 25 cf. pp. 34-36.) In the words of von Franz, the Se of INJs is often “terribly immoderate” in one direction or another and so the standard behavioral indicators of inferior Se is either extreme sensory indulgence or an ascetic world-denial; “a starving of the senses.” Sometimes the two extremes can even be united in the same person, as in the case of Nietzsche who was in the main sexually abstinent and homeless, but was at the same time extremely sense-indulgent when it came to music, art, and food. With regards to Plato, we find that he was extremely world-denying and that he actually speaks directly of “starving the senses” in more places than one. It would be unlikely, then, for Plato to casually adopt sensory empiricism the way some Revisionists claim he had done (and even more unlikely that such a shift would have gone unmentioned in the testimonies on Plato, had it taken place).