By Ryan Smith

“No one can foresee in what guise the nucleus of truth contained in the theory of Empedocles will present itself to later understanding.” – Freud: Analysis Terminable and Interminable §6

Empedocles (ca. 490-430 BCE) is the earliest Western thinker to whom Freud ever referred.[1] Just as Heraclitus was Jung’s favorite  pre-Socratic, so Empedocles was Freud’s archaic muse. Like Freud, Empedocles was not only a theoretical thinker, but also a practical healer. Both men drew a substantial part of their identities from being physicians (or at least from considering themselves as such) while at the same time both of their oeuvres went far beyond the scope of pursuits that were purely medical.

pre-Socratic, so Empedocles was Freud’s archaic muse. Like Freud, Empedocles was not only a theoretical thinker, but also a practical healer. Both men drew a substantial part of their identities from being physicians (or at least from considering themselves as such) while at the same time both of their oeuvres went far beyond the scope of pursuits that were purely medical.

Here are three ways in which Empedocles influenced Freud.

1: Metaphysical Orientation

“People are seldom impartial where ultimate things, the great problems of science and life, are concerned. Each of us is governed in such cases by deep-rooted internal prejudices, into whose hands our speculation unwittingly plays.” – Freud: Beyond the Pleasure Principle (SE 18:59)

While Heraclitus and Jung were non-materialists, seeing something mental or non-material as the prime element of the cosmos, Empedocles and Freud were both predisposed to materialism, essentially perceiving the psyche (and all other life in the universe) as nothing but living, animated matter.

Freud is quite correct to say, as I have quoted above, that personality and psychological makeup predisposes a person to a certain metaphysical orientation. In terms of Jungian typology, such prejudices will often be found to fall along the lines of types with Te and Fi being materialists (or something akin to materialists) while types with Ti and Fe will more often be found to be non-materialists.[2]

There are authors who, by way of blind extrapolation of the Jungian concepts, assume that materialism must be a feature of extroversion and/or a preference for sensation. In my experience I have never found this to be true. Indeed, behind such an assumption a condescending and simplistic attitude towards extroversion and sensation is often to be found, as well as an ill-disguised arrogance towards the materialistic standpoint.

I must confess that I do not know exactly why attitudes towards materialism should be split across Te-Fi / Ti-Fe lines. But I venture the following guess:

Ontological Prejudice of the Functions

Ti: Does not naturally perceive phenomena in terms of matter, but rather in terms of the abstract, subjective idea which the individual phenomenon represents. The elements of physical existence that do not fit with the pursuit of the abstract idea are ignored or neglected (e.g. “it is a nonessential feature, let somebody else take care of that”). The abstract idea that is pursued by Ti is immaterial; it is imagined rather than proven; it is a possibility, not a necessity. It follows that matter appears as a necessity – a stricture upon the idea that the Ti type feels inclined to look beyond or break out of.

Fe: Does not naturally perceive phenomena in terms of matter, but rather in terms of the sentiments that they elicit in the psyche. There is a tendency to perceive objects as sentient beings to be sympathized with (e.g. “the Earth has a soul”). Consciousness is thus unwittingly ascribed a primacy over matter. Of course we are made up of both consciousness and matter. But according to the Fe prejudice, our defining feature is our consciousness – the awareness that experiences sentiments.

Te: Does not naturally perceive phenomena in terms of events, but in terms of objective laws that standardize and shut out that which does not confirm to the law (Psychological Types §585). Overarching ideas like “energy” and “matter” allow for the greatest extension of such laws into all spheres of human existence, including psychic life. Matter is therefore unwittingly accepted as holding the primacy over consciousness; consciousness is just matter experiencing itself. It follows that sentiments and feelings, which are personal and illogical, and which no known law can sort out, are the accidental and secondary features of existence.

Fi: You have your values, and I have my values. But you are not me. We each experience our highest values through our own personal, subjective psyche. I cannot adjust my innermost, truest ideas to fit with yours, nor can you adjust yours to fit with mine. We are not to place demands upon each other, but to tolerate each other the way we are, so that we are both free to go our own way. Thus we cognize our deepest thoughts and feelings through the purity of our own subject. A great gulf separates your innermost nature from mine; this gulf may be material in nature, or it may not. All I know is that it is there.

I would posit that just as Jung and Heraclitus joined forces to throw their weight behind the ontological prejudices of Ti-Fe, so Empedocles and Freud shook hands on the importance of the Te-Fi worldview.[3]

Jung often championed his idea of a Collective Unconscious as an innovation that Freud had not seen coming, but a close reading of the Freudian corpus reveals that Freud actually did have some conception of a collective unconscious. The difference was not nearly as great as Jung would make it out to be, but there was a small difference. For Freud, being a materialist, the Collective Unconscious would only extend to your personal ancestors, who may be assumed to have passed some of their own essence down the generations, so that some of the specific genes they had may be found in your own genome. In this way, the nature and extent of Freud’s concept of the Collective Unconscious adheres strictly to the restrictions of materialism: Any collective features harbored by the Collective Unconscious must have been transmitted through matter (genes) and been inherited from specific ancestors.[4] In the Freudian sense, one person’s Collective Unconscious may thus be very similar to or completely different from that of another, depending on the number of ancestors they share.

By contrast, Jung’s concept of the Collective Unconscious is ultimately one that is shared amongst all mankind, the psychic contents transmitting themselves from one person to the next through the medium of archetypes.[5]

Please note that I used the word predisposed and not predetermined to describe how some functions more easily lend themselves to certain ontological prejudices than others. The orientations given above are far from perfect correlations. Most notably, Heraclitus himself was no materialist, although I conjecture that he had Te and Fi.

2: Cosmological Dualism

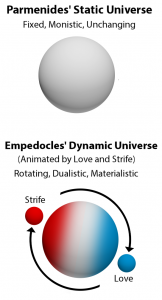

In ancient philosophy, Parmenides had posited that everything in the cosmos was a giant, static sphere completely devoid of movement. In the ancient sources, we are told (by Simplicius in Diels 31 A7) that Empedocles was an associate and imitator of Parmenides. I contend that Empedocles inherited the idea of the universe as a static sphere from Parmenides, but then appropriated it for his own purposes. He did so by adding two primordial and transcendent principles to the sphere, namely Love and Strife.

In ancient philosophy, Parmenides had posited that everything in the cosmos was a giant, static sphere completely devoid of movement. In the ancient sources, we are told (by Simplicius in Diels 31 A7) that Empedocles was an associate and imitator of Parmenides. I contend that Empedocles inherited the idea of the universe as a static sphere from Parmenides, but then appropriated it for his own purposes. He did so by adding two primordial and transcendent principles to the sphere, namely Love and Strife.

Love and Strife can never be united; they spin around the sphere, and it is this centripetal activity that causes movement and activity, cessation and arising, and life and death to occur in the universe. Under Love, all creatures are brought together in harmony and procreation. Under Strife, the same creatures wage war against and fight each other, exhibit aggression towards one another, and die.[6]

Freud, for his part, was naturally sympathetic to the idea that a great Love-force was really at the root of everything we do. He just preferred to think of it as an erotic force instead, a Sex-force, as it were. But through his experience with patients, who exhibited all manner of survival-negating behavior like masochism and substance abuse, Freud was driven to postulate that, besides the Life-force found in Love, we are also governed by a Death-force found in Strife.

The dualistic principles of Freud and Empedocles are thus synonymous with each other:

Empedocles

Love and Strife

Freud

Eros and Death

To Freud it was obvious that our aggression must be governed by something outside of ourselves; the transcendent principle of Strife or the Death-drive. He found evidence for this idea by noting how humans do not just aggress against each other, but how they also aggress against themselves. That they self-sabotage, as it were. To Freud, this self-destructive behavior makes it clear that we are not the masters of our own aggression, but that some outside force is driving it.

Thus both Freud and Empedocles would maintain that the ultimate nature of the universe can only be known through a dualism: a union of Love and Strife, where one implies the other.

One might say that this dualism is reminiscent of the way the functions imply the opposites in Jung (e.g. Ni always implies Se). However, to say so would not be quite true: In a dualism, two opposite principles may imply one another, but they are also considered completely distinct. The way Freud and Empedocles saw it, Love and Strife will always be distinct from each other, just like the identical poles of two magnets will always repel each other and mutually keep each other at a certain distance.

But the view of Jung and Heraclitus is different. Their view is rather a non-dualism where two opposing principles will really be found to be the same thing when examined closely. A favored Jungian symbol of this non-dualism is the Ouroboros – the alchemical symbol of the snake that is chasing its own tail. The snake is constituted by both its head and its tail, just like, say, an INJ type is constituted by both superior Ni and inferior Se. Without one of these parts we would not have the whole. Unlike the dualistic view of Freud and Empedocles, Jung and Heraclitus did not consider the opposites to be distinct.

This observation gives us recourse to return to the point about how the functions predispose the psyche to certain ontological convictions: In the Te-Fi mode of consciousness, one will naturally be inclined to perceive the world in terms of distinct entities that are judged according to black and white. But in the Ti-Fe psyche, objects are often perceived as interwoven and assessed according to shades of grey.

It follows, then, that just like Fi-Te types are predisposed to materialism and Fe-Ti types to non-materialism, so Fi-Te types are predisposed to ontological dualism, while Fe-Ti types are predisposed to ontological non-dualism.[7]

***

How did Empedocles furthermore influence Freud? That question will be answered in Part 2 of this essay.

***

Image of Empedocles in the article commissioned from artist Francesca Elettra.

NOTES

[1] Askay & Farquhar: Apprehending the Inaccessible p. 55

[2] In the same way, NTP types are often metaphysically prejudiced in favor of the Kantian Noumenon while NTJ types are prejudiced against it.

[3] The question of whether Freud was really a full-blooded materialist is actually quite complex. Several writers have remarked on how Freud’s ontology seems suspended between the materialist and mechanistic causalities that were considered “scientific” in his time on the one hand, and then a literary, philological, and mythological worldview on the other, which seems to have its roots at least partly in Freud’s own person. A purely historical, impersonal fact, which seems hard for us to understand today, may shed some further light on this matter: In Freud’s and Jung’s own times, the Germanic fascination with ancient Greece was so predominant that even the natural sciences were sometimes taught according to philological and philosophical methods, rather than according to the experimental and empirical approach that drives the natural sciences today (Noll: The Jung Cult p. 307n47). However, even when taking this little-known historical fact into account, there is still an unmistakable trace of Freud’s own personality and character in the literary aspirations that are so ubiquitously featured in his work.

[4] Nagy: Philosophical Issues in the Psychology of C.G. Jung p. 131

[5] Jung also felt that the individual’s Collective Unconscious could be either closer to or further from specific archetypes, depending on that person’s nationality and race. However, he did not agree with Freud that the workings of the Collective Unconscious could be confined within the strictures of materialism.

[6] Though Parmenides was probably not a materialist, Empedocles was. To Empedocles, the static sphere, without the centripetal, rotating forces of Love and Strife, would thus consist of nothing but cold, dead matter. It is the centripetal activity of Love and Strife that animates matter and makes it come alive, thus creating consciousness. It follows, then, that matter is more inherent to existence than consciousness.

[7] It often happens that sources on Jungian typology contend that Ni is the non-dualistic and synthetic function par excellence, but I have never found that Ni had any such advantage over Ne. However, not being bound to reality, but being bound to inner mental images instead, it is clear that both Ne and Ni are more synthetic and “non-dual” than the corresponding S functions. On this point, I quote Freud himself who, contrasting himself with Jung and Adler, said: “I so rarely feel the need for synthesis. The unity of this world seems to me something self-understood, something unworthy of emphasis. What interests me is the separation and breaking up into component parts what would otherwise flow together into a primeval pulp” (Freud, quoted in Mazlish: The Leader, the Led, and the Psyche p. 49). In other words, the non-dualistic perspective, which was so highly prized by Jung and Heraclitus, and which frequently featured as the end product of their endeavors, was simply too banal, too “self-understood” to the sensible Freud.