Academically reviewed by Dr. Jennifer Schulz, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology

Moral Circles Test

Social psychologists Waytz (Northwestern University), Iyer (University of Southern California), Young (Boston College), Haidt (New York University), and Graham (University of Southern California) published a landmark study in Nature on the “moral circle”—the boundary people draw around those they consider worthy of moral concern. Their research showed that liberals and conservatives differ not only in which moral values they emphasize, but also in how far outward they extend compassion and care. This test is inspired by their work. It invites you to map your own moral circles by deciding who—and what—you extend your moral concern to.

Question 1 of 1

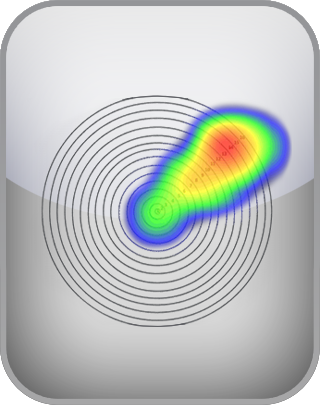

You have 100 units of moral concern to allocate to various circles. Distribute them to show your empathy and concern. Allocating points to a higher-level circle does *not* include the lower ones.

FINISH

In 2009, Jesse Graham, Jonathan Haidt, and Brian Nosek published a landmark study titled Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. This article has become one of the most widely cited works in moral psychology and political psychology because it provides a systematic explanation of how liberals and conservatives approach morality in distinct ways. The study is grounded in Moral Foundations Theory (MFT), which posits that human morality is built upon several evolved psychological systems or “foundations.” These foundations help people evaluate right and wrong, but not all groups prioritize them equally.

According to MFT, there are five primary moral foundations: harm/care, fairness/reciprocity, ingroup/loyalty, authority/respect, and purity/sanctity. Harm and fairness are often called the “individualizing” foundations, because they emphasize the protection of individuals and their rights. Ingroup, authority, and purity are often termed the “binding” foundations, because they focus on group cohesion, social order, and the regulation of behavior to preserve community values. Graham and colleagues hypothesized that liberals and conservatives differ in the relative importance they assign to these foundations. Specifically, liberals would prioritize harm and fairness above the others, while conservatives would distribute their moral concerns more evenly across all five.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers collected data from large samples using the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ), an instrument designed to measure the degree to which individuals endorse each foundation as relevant to moral judgment. The study drew upon tens of thousands of participants, many of whom were recruited through the Project Implicit website, an online platform for psychological research. This broad and diverse dataset allowed the authors to examine ideological patterns across a wide spectrum of respondents.

The results strongly supported the predictions. Liberals consistently rated harm and fairness as far more relevant to their moral decision-making than loyalty, authority, or purity. In contrast, conservatives gave relatively equal weight to all five foundations, indicating that their moral reasoning rested on a broader set of concerns. Moderates fell between the two groups. Importantly, these differences were not trivial; they were robust across demographics and persisted even after controlling for potential confounding factors. The study concluded that the moral divide between liberals and conservatives is not simply a matter of disagreement about facts or policies but reflects deeper, intuitive differences in moral psychology.

The implications of these findings are far-reaching. First, they help explain why political debates in the United States and elsewhere often feel intractable. Each side appeals to moral values that resonate strongly with their own group but may fail to connect with the moral priorities of the other. For instance, a liberal might argue against torture by emphasizing the harm it inflicts on individuals, while a conservative might justify harsh treatment of enemies in the name of loyalty or purity. Both arguments are moral, but they rest on different foundations.

Second, the study provides a framework for bridging ideological divides. By recognizing that conservatives and liberals are not simply “more” or “less” moral but rather moral in different ways, it becomes possible to foster greater mutual understanding. Political persuasion, for example, may be more effective when arguments are framed in terms of the audience’s moral foundations rather than one’s own.

Finally, the study has influenced research beyond psychology, including political science, sociology, and communication studies. Moral Foundations Theory is now widely used to analyze political rhetoric, design interventions for reducing polarization, and study cultural differences in moral reasoning.

In summary, Graham, Haidt, and Nosek’s (2009) work demonstrates that liberals and conservatives emphasize different moral domains, with liberals focusing heavily on harm and fairness, and conservatives balancing all five. This insight has shaped contemporary discussions about morality and politics, highlighting the psychological roots of ideological conflict and offering new avenues for dialogue.

References

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1029-1046.

- Waytz, A., Iyer, R., Young, L., Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2019). Ideological differences in the expanse of the moral circle. Nature Communications, 10, Article 4389.