In Part 1 of this essay, we looked into some of the philosophical reasons why Freud might have found himself attracted to Empedocles. Here in Part 2, we will focus on the psychological reasons instead.

3: Personal Attraction

Freud felt a sense of personal admiration for Empedocles. In my opinion, Freud’s admiration for Empedocles was not just a case of intellectual admiration akin to the way that a non-Nietzschean may still admire Nietzsche. I contend that it is obvious that in Freud’s case, a personal attraction was also in play. Here is Freud’s characterization of Empedocles:

Freud felt a sense of personal admiration for Empedocles. In my opinion, Freud’s admiration for Empedocles was not just a case of intellectual admiration akin to the way that a non-Nietzschean may still admire Nietzsche. I contend that it is obvious that in Freud’s case, a personal attraction was also in play. Here is Freud’s characterization of Empedocles:

“[Empedocles] is one of the grandest and most remarkable figures in the history of Greek civilization. The activities of his many-sided personality pursued the most varied directions. He was an investigator and a thinker, a prophet and a magician, a politician, a philanthropist and a physician with a knowledge of natural science. He was said to have freed the town of Selinunte from malaria, and his contemporaries revered him as a god. His mind seems to have united the sharpest contrasts. He was exact and sober in his physical and physiological researches, yet he did not shrink from the obscurities of mysticism, and built up cosmic speculations of astonishingly imaginative boldness.” – Freud: Analysis Terminable and Interminable §6

Like Freud, Empedocles walked a tight-rope line between myth and science. Freud saw himself as a scientist, but he eagerly appropriated myth for his own use (e.g. Oedipus). However, for outward purposes, Freud was always at pains to make his findings appear as the result of long and careful deliberations. This approach marks a manifest contradistinction to Empedocles, whose method was marked by an “astonishingly imaginative boldness”; a man who gave us “phantoms and fables … in a wild state of exaltation.”[1]

What might explain this attraction between Freud, the adherent of the sure and cautious approach, and the motley and chromatic Empedocles? Two avenues of interpretation present themselves: One has to do with personality styles, the other with personality types.

Freudian (Style) Interpretation

In terms of personality styles, I assert that Freud had a dominant Compulsive style with auxiliary Narcissistic traits.[2] According to the work of Theodore Millon, the Compulsive-Narcissistic personality style is usually characterized by deriving a sense of identity and security from the rules of a group, as well as by being “empowered by formal organizations; … officious [and] high-handed…”[3]

In writings about Freud’s personality, his Narcissistic traits are often accentuated. But based on my own research, I believe that Freud’s Narcissism was only auxiliary. If one giveaway to the Compulsive-Narcissistic style is that the person derives a sense of identity and security from a group, then Freud’s tendency to feel empowered through a group identity can be seen in the way he hides his personal subject throughout his writings. For example, Freud frequently refers to “the findings of psychoanalysis” when he is really referring to “the findings of Freud.” Likewise, Freud frequently refers to “what psychoanalysis thinks” when he really is talking about what he thinks.

Millon’s description of the Compulsive-Narcissistic personality style goes on: “Unimaginative … petty-minded … trifling [and] closed-minded.” Now, it would hardly make sense to call one of the greatest minds of the 20th century closed-minded or petty. But Millon’s prescription is nevertheless true in the sense that Freud always wanted to reduce complicated phenomena to something smaller and simpler, such as wanting to make everything about sex or wish fulfillment.[4] In his theorizing, he preferred to move from the whole to the part, from the intricate to the plain.

It is the tendency to reduce the complex to the simple that makes Freud a master detective, attuned to the finest details of a situation. But on the other hand, the same tendency also makes him appear mundane, as the ultimate questions of existence are invariably reduced to primitive instinct.

Now, if we analyzed Freud through the use of personality types, we would say that Freud was an STJ, and that that is just how STJs are. Jung seemingly said just that, when he believed that Freud was an ST type.[5] Yet this assertion is far from fair to STJs, for while such characteristics do not apply to all STJs, they do apply to all Compulsives. So let’s look into Freud’s Compulsive style.

Compulsive (Dominant)

The Compulsive style is characterized by the need for order, control, and familiarity. The Compulsive personality has extremely high outer standards, which he cannot switch off. Inside, he is constantly repeating certain mantras to himself: “I must give all that I can give to be accepted.” – “Nothing I do is ever good enough.” – “I must look my best in the eyes of others at all times.” – “I must take care of my duties so that I am above criticism.” – “I cannot afford to relax.” – “Things must be right in my life.” – “I must not make mistakes.”[6]

In a word, the Compulsive suffers from unrelenting standards that he constantly and obsessively batters himself with on the inside. Let me offer some examples of how I believe the evidence supports the view that this style applies to Freud:

“One of [Freud’s] ‘obsessions’ was that anything out of the ordinary, unexpected, and not ‘guarded against’ roused anxiety and discomfort.” – Paul Roazen: How Freud Worked, Chapter 8

“Freud’s ‘obsessionality’ was expressed in all his being. He needed that immense amount of self-control and discipline.” – Paul Roazen: How Freud Worked, Chapter 8

“I asked [Freud’s patient Hirst] whether he had ever found it frustrating that everything with Freud had to be so exact. Hirst [recalled] how the collection of antique figures on Freud’s desk was always in the same order.” – Paul Roazen: How Freud Worked, Chapter 1

“[Freud] saw four or five patients in a row from 8 or 9 a.m. till 1 p.m., day after day, and then several more in the afternoon until he had a late supper, and two nights a week he lectured at the university, while Wednesday evenings were reserved for the Psychoanalytic Society. He had no secretarial help, wrote all of his many letters by hand, and [also] wrote a large number of seminal books and essays.” – Walter Kaufmann: Discovering the Mind vol. III p. 232

“Even Freud’s mustache and pointed beard were subdued to order by a barber’s daily attention. Freud had learned to harness his appetites. … [He had] chained [himself] to a most precise timetable. … ‘He lived’ … ‘by the clock.'” – Peter Gay: A Life for Our Time p. 157

“[Even Freud’s] leisure time and summer vacations were carefully organized and predictable.” – V.W. Odajnyk: Archetype and Character p. 91

With these testimonies (many of which hark back to the eyewitness accounts of people who knew Freud personally) I submit that Freud’s dominant personality style was Compulsive. However, as I said, he also had an auxiliary Narcissistic personality style.

Narcissistic (Auxiliary)

Freud also had a Narcissistic style, but this style was subdued and played second fiddle to his dominant Compulsion (indeed in my opinion, Jung’s Narcissistic style was far more pronounced than Freud’s).

A Narcissistic personality style refers to a pattern of seeking excessive admiration and validation from outside sources. Simultaneously, a Narcissist is apt to take extreme pride in himself and speak highly of his own abilities. A Narcissist tends to believe that life has great things in store for him. He feels entitled, as if he is special, above the rules, and superior to others. And a Narcissist is usually extremely sensitive to criticism of his work or person.

As I mentioned before, when authors set out to describe Freud’s personality style they often conclude that he was a Narcissist on account of his inability to tolerate disagreement and divergence within the psychoanalytical movement. Oddly enough, his Compulsive traits are often passed by in silence or at the very least it is rarely considered whether Freud’s controlling behavior may be better chalked up to a Compulsive style than a Narcissistic one.

However, my disagreement with the general tenor of the assessments of Freud’s personality style extends no further than to the prominence of his narcissism, for he was indeed Narcissistic. I simply say that, as opposed to a true Narcissist who effortlessly flaunts grandiose notions about his own self-worth, Freud subdued and tucked away his narcissistic grandiosity. The following quote will illustrate my assessment:

“Do you know what Breuer said to me one evening? … He said that he had found out that there was concealed in me under the shroud of shyness an immeasurably bold and fearless human being. I have always believed this myself and never dared to tell anybody. … But I could not give expression to my ardent passions … so I have always suppressed myself, and that, I think, must show.” – Freud: Personal letter to his wife[7]

So by Freud’s own admission, there was a grander and more unconstricted self inside of him, which he did not have the courage to express. To do justice to his grandiose sense of self, Freud would have to find other means of expression by which the grandiosity could come out. What might these means of expression have been?

As I have already hinted, one way to spot the Compulsive-Narcissistic personality is that the person hides his true personality from the line of fire because he is plagued by a sense of personal vulnerability (indeed, he is afraid of being rejected; of being thought “not perfect”). As a recourse, the Compulsive-Narcissistic personality advances his personal viewpoints as if they were the shared beliefs of a group or organization.[8] In Freud’s case, this “group or organization” was the discipline of Psychoanalysis, which he used as an avatar to expand and empower his sense of self.

Empedocles as an Example of the Histrionic Personality

To recap, my point here is to argue that Freud felt a sense of personal attraction to the works of Empedocles. Under the preceding three headings I have argued that Freud’s personality style was a Compulsive-Narcissistic one, and so we are now in a position to relate this insight to why Freud might have felt this sense of attraction when he studied Empedocles.

While Freud’s personality style was Compulsive-Narcissistic, the style of Empedocles was primarily Histrionic.[9] In brief, the Histrionic personality is characterized by a great need for being around people and a love of being the center of attention. Histrionics have a high level of sensitivity (especially concerning what others think of them), but this sensitivity is not well integrated with the critical faculties of the psyche.[10] The result is that the Histrionic is tossed from sensation to sensation in a series of shifting shallow images, as if they were partaking in a movie that had little connection between one scene and the next.[11] What they say at one moment may not necessarily hold true for the next.

Histrionics constantly fear rejection, and so they have learned to develop a great deal of charm. Their need for acceptance and attention will frequently also lead them to adopt attention-grabbing maneuvers such as flamboyant clothing or sexualized behavior.[12] The survival strategy of the Histrionic relies on the reasoning that as long as they can keep eliciting attention and acceptance from their surroundings, they can reassure themselves that they are lovable and acceptable (even if this reassurance is only fleeting to them).

Another feature of the Histrionic personality is their inconstancy: Like Borderlines, Histrionics can jump from black to white with little need for grey in between. The Histrionic does not enter into a conversation thinking, “What is my viewpoint?” but rather, “What do I need to say to win acceptance and admiration?” Because they are really more concerned with being accepted than with asserting their own views, Histrionics are prone to exaggerate their response to input in a conversation and make them appear as spur-of-the-moment reactions. By doing so, they are tacitly reserving the right to reverse their response if it fails to strike a chord with the listener (“Oh, I didn’t really mean that. I can’t be pinned to what I said, I just said it on a whim”).

Among clinical psychologists it is well-known that if the Histrionic personality is endowed with intelligence, he or she may be remarkably creative in producing rich combinations of intellectual and artistic sensibility.[13] (Although as with so much else in the field of psychology, Nietzsche beat the “psychologists” to this insight, just as he beat the psychologists to the use of “their” own title.)[14] The reason for the remarkable creativity of the intelligent Histrionic stems from the fact that his cognition disengages from the intellect’s critical faculties. This disengagement allows a remarkable flow of fantasies and intuitions to come through to consciousness and to be expressed agreeably and artistically and with little thought given to self-criticism or coherence. It is this immediacy, this lack of critical reserve, which allows the Histrionic personality to give expression to insights which others may also cursorily glean, but which the non-Histrionic’s critical faculties would soon strike down or dismiss.

On account of these observations, I submit that Empedocles was such an unusually intelligent and highly gifted Histrionic individual. My claim is supported by the following passages:

“The highly poetic and emotive language of [Empedocles’] verse has led not only to problems of interpretation, but also to a number of textual difficulties.” – Robin Waterfield: The First Philosophers p. 133

“[Empedocles moved about] in a grand and striking manner, he wore a gold wreath on his head, a purple robe with a golden girdle, and bronze sandals.” – Constantine J. Vamvacas: The Founders of Western Thought p. 137

“Empedocles is unusually catholic [i.e. all-embracing] in his theories and tastes.” – Daniel W. Graham: The Texts of Early Greek Philosophy vol. I p. 327

“[Empedocles] gives us phantoms and fables … in a wild state of exaltation.” – Plutarch: Moralia §7

“All hail! I go about you as an immortal god, no more a mortal, so honored am I by all I meet, I am crowned with fillets and flowery garlands. Straight away as soon as I enter a city with these, men and women flock to me, I am revered and tens of thousands follow.” – Empedocles: Fragment DK 31 B112

If the assertion that Empedocles was Histrionic in nature holds true, an implication for philosophy is that attempts to reconcile the contradictions in his work by working out “what Empedocles really meant” are bound to be spurious. But with regards to our purposes here, Freud did not attempt to reconcile the contradictions in Empedocles’ thinking, but rather reveled in them, and celebrated them as romantic fantasies. Why was Freud so enamored of this thinker whom other thinkers would label a charlatan?[15]

Freud’s Attraction to the Histrionic Personality

When Freud wrote Analysis Terminable and Interminable (the text in which he adulates Empedocles at length), he was an old man near to the end of his life. However, even prior to committing his passion for Empedocles to writing, Freud had exhibited a consistent pattern of admiration for, and attraction to, the Histrionic personality:

“[Ruth Brunswick] was charming and explosive, very intelligent as well as vivacious, and Freud liked her a great deal.” – Paul Roazen: How Freud Worked, Chapter 8

“[Freud’s favorite] was Ruth Brunswick. … She had a ‘courageous’ mind… She was not ‘restricted’ the way most people were. … She would [incessantly] change her mind. … She had the courage to behave that way with Freud. … Few people brought that same ‘freedom’ to him. … It was ‘pure pleasure on both sides.'” – Paul Roazen: How Freud Worked, Chapter 7

“[Freud’s friend] Fleiss was a very charming and vivacious man and Freud had a need and a terrible weakness for that kind of glamorous person. When Jung came along, he became that person again for Freud. Both Fleiss and Jung were charlatans in some ways, but very bright, very beguiling ones.” – Leonard Shengold[16]

Why was Freud so attracted to Histrionics? The answer falls in two parts and may be traced back to both of Freud’s personality styles.

The Compulsive’s Attraction to the Histrionic Personality

1. Reprieve and acceptance.When psychologists set out to map the etiology of the Compulsive personality, their patients often report that they had a strict parent who placed severe demands on them from a young age. In adulthood, these people still go through life with a parental figure on their shoulder, scolding them, disciplining them, and criticizing them for their mistakes. Of course, the actual parent has long since left their daily lives, but through the many years of criticism, the Compulsive has learned to internalize the criticism and self-blame.[17] Wherever they go, their strict mother or father follows them. They have become their own worst critic.

To the Compulsive, the good-natured egocentricity of the Histrionic represents a reprieve from the demands of the critical parent. Obviously, the Histrionic personality wants acceptance; to be deemed lovable and “good enough.” But less obviously, so does the Compulsive. As opposed to the demanding parent, whose love can never really be won no matter how hard the Compulsive works, the “demands” of the Histrionic are blatantly obvious: “Notice me, celebrate me, and like me, and I will like you right back. I am a fickle personality who cannot take care of myself and so I will always be there at your side if you take care of me.” Recall also that the Compulsive seeks to rise above the criticism of the demanding parent by exerting a sense of control over everything in their life. When the Histrionic communicates a sense of being unable to manage himself, he is in fact letting the Compulsive know that he can count on his tenderness, indeed control his affection.[18]

2. Entertainment. In terms of their modes of thought, Histrionics tend to be imaginal and global, whereas Compulsives tend to be factual and local. Colloquially we may say that they are “flashy” and “boring,” respectively. In Freud’s case there is good reason to assume that he admired and was entertained by the flighty and colorful character of Empedocles. Indeed, in Freud’s own words, he saw the philosophy of Empedocles as a beautiful and beguiling fantasy – a romantic disposition of the kind which so evidently attracted him to Brunswick, Fleiss, and Jung, but which he was wholly unable to give voice to himself.

I have already hinted that not just Empedocles, but Jung too, had Histrionic traits. Indeed, though his errand was not to examine their personalities, the philosopher Walter Kaufmann has remarked on how this classical give-and-take between the Compulsive and Histrionic was also applicable to the Freud-Jung relation when he said: “Freud … sets standards … that we can hardly hope to satisfy. … Jung makes no demands on us. He provides diversions and escapes.”[19]

The Narcissist’s Attraction to the Histrionic Personality

But Freud was not just Compulsive; he was also Narcissistic. So this naturally prompts the question of what the Narcissist sees in the Histrionic:

1. Self-object. A commonly-recognized feature of Narcissism, which dates back to the theories of Heinz Kohut, is that Narcissists who are unable to directly manifest the grandeur which they connect with their sense of self are bound to find some other person who can assert that grandeur and then to identify the self with that other person. The other person thus becomes a self-object; an object that completes the Narcissist’s sense of self. According to Kohut, in order to be regarded as a self-object in the eyes of the Narcissist, the other person should avoid challenging the Narcissist’s grandiosity, but play along and allow it to flourish. And as we have seen, the chief concern of the Histrionic in a conversation is not to challenge, but to secure acceptance and approval from the other. The Histrionic can therefore easily come to be seen as a self-object, as he appears to be saying exactly what the Narcissist wants to hear: That he or she really is supreme.

In Freud’s case, he was evidently impressed by the fact that the Greeks considered Empedocles a god. As we have seen, Freud believed that under his own shyness and constriction there lived “an immeasurably bold and fearless human being.” With regards to the Narcissist’s tendency to turn people possessing the qualities that they feel are lacking in themselves into self-objects, it is hard to escape the thought that identification with the unconstricted and vivacious Empedocles, who was exuberant enough to declare himself a God, did in some sense complete Freud’s sense of self.

In the case of Freud’s alternating Narcissistic attraction to the various Histrionic figures in his life (e.g. Jung, Fliess, Ruth Brunswick, and Empedocles), the constricted person (Freud) knows that he cannot live out his personal fantasies of being unconstricted, vivacious, vibrant, spirited, bubbly, and the like. So he throws his “love” at a glamorous other who can. This other then becomes an object; a fetish that completes the self. Specifically, with regards to Freud’s’ attraction to Empedocles, the qualities that attracted Freud were (a) the social vivaciousness, which Freud himself lacked, and (b) the grandiose audacity to openly declare himself a god, which Freud would in some sense have liked to do, but did not dare to. (Recall Freud’s fantasies of personal flawlessness and of being “an immeasurably bold and fearless human being.”)

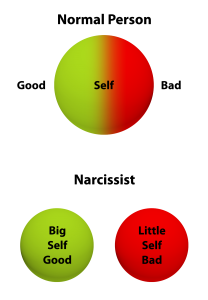

2. The depreciated, ”little” self. Another central theme of the Narcissistic condition, which Otto Kernberg was amongst the first to see, is that the Narcissistic person is really split between two selves: Of course they have the grandiose and perfect “big” self, which is the “default” self that the Narcissist shows the world as a façade. But underneath the big self is a “little” self, which is the shameful and underdeveloped self which led the Narcissist to develop the artificial grander self in the first place.[20] As the psychologist John Berecz has pointed out, the Narcissist’s self-image is therefore “hovering between Hollywood and hobo” – between the grandiose “big” self and the shameful “little” self.[21] In normal people, awareness of the good and bad sides of their person is integrated into their overall sense of self. But in Narcissists (as well as in Borderlines), the good and the bad are polarized into distinct selves which do not speak together and between which there is no middle ground (it’s either Hollywood or hobo).

2. The depreciated, ”little” self. Another central theme of the Narcissistic condition, which Otto Kernberg was amongst the first to see, is that the Narcissistic person is really split between two selves: Of course they have the grandiose and perfect “big” self, which is the “default” self that the Narcissist shows the world as a façade. But underneath the big self is a “little” self, which is the shameful and underdeveloped self which led the Narcissist to develop the artificial grander self in the first place.[20] As the psychologist John Berecz has pointed out, the Narcissist’s self-image is therefore “hovering between Hollywood and hobo” – between the grandiose “big” self and the shameful “little” self.[21] In normal people, awareness of the good and bad sides of their person is integrated into their overall sense of self. But in Narcissists (as well as in Borderlines), the good and the bad are polarized into distinct selves which do not speak together and between which there is no middle ground (it’s either Hollywood or hobo).

With regards to the Histrionic personality, it has often been remarked how the Histrionics can be quite deficient in the empathy department.[22] Histrionics typically have a lot of affective empathy, that is to say, they know how to respond appropriately to the immediate situation in an emotionally appropriate way. For example, if someone is suffering a setback right before their eyes, Histrionics typically know how to respond with the appropriate emotional reaction (whereas Narcissists typically do not).

However, with regards to cognitive empathy, Histrionics tend to be deficient. Cognitive empathy refers to an intellectually-driven “thinking into” the other person.[23] (A well-developed faculty for cognitive empathy is also one of the essential qualities required to accurately determine someone’s Jungian type.) It is through cognitive empathy that one person represents for himself what it must be like to be the other person. It is by using cognitive empathy that we watch the other person from the inside, and not just from the outside.

We have already covered how the Histrionic person is flighty and concerned with being noticed and making an impact rather than reflecting on his own opinions in depth. Consequently, the Histrionic typically has little facility for cognitive empathy. He takes his cues about other people “from the outside” and tends to see the façade rather than “thinking into” the underlying personality that produced the façade.

Thus, when the Histrionic interacts with a Narcissist, he tends to accept the grandiose façade of the Narcissist at face value. Because the Histrionic personality is deficient in cognitive empathy, he does not get the “horse sense” sensation that something is amiss with the Narcissist. Even if other people are not able to articulate it, they still tend to notice that something is contrived about the Narcissist. The Histrionic, having little facility in the way of cognitive empathy, does not.

By fraternizing with the Histrionic, the Narcissist will have his grandiose (but contrived) facade reflected back to him. If the Narcissist is normally suspended between Hollywood and hobo, he will, in the Histrionic, appear to have found someone who confirms to him that he is all Hollywood, all the time. And the Narcissist, possessing poor internal judgment, eventually begins to think that he really is all Hollywood, since it is obviously plain for the trusted Histrionic to see.

In the case of Freud and Empedocles, it is hard to argue that the reason Freud was so attracted to Empedocles was because Empedocles reflected Freud’s own grandeur back to him. It is far more cogent to argue that Freud’s attraction stemmed from a sense of personal identification with, and self-objectification of, Empedocles as we have done above. However, the mechanism of using the Histrionic as a prop to reinforce one’s grand self was still prevalent in Freud’s life. In the period of Freud’s and Jung’s friendship (1906-1913), Jung passed through a period of Histrionic idealization of Freud where he, amongst other things, spoke of Freud in messianic terms.[24] Yet ultimately, Jung had Narcissistic traits as well, which left him dissatisfied with the role of Histrionic squire.

Jungian (Personality Type) Interpretation

So much for Freud and Empedocles in terms of styles. What may we say of their relation in terms of types?

Around the time where he wrote Psychological Types (1921), Jung had believed that Freud was an EST. However, by 1957, Jung revised his view and would now claim that Freud had secretly been an INFP the whole time, but had struggled to present himself as an EST all his life.[25] If we accept Jung’s assertion, we may surmise that Freud was attracted to NFPs who indulged in their natural NFP-ness because Freud suppressed these inclinations in himself.[26]

Both the style as well as the type interpretation, each being psychodynamic in origin, thus assert that Freud’s attraction to Empedocles stemmed from coveted or suppressed elements of Freud’s own personality that he could not express directly. According to the style interpretation, it was Freud’s grandiose and Narcissistic self that he saw reflected in Empedocles, and according to the type interpretation, it was Freud’s intrinsic NFP-ness that he was ashamed to live out.

Another perspective yielded by the prism of types can be found if we forgo Jung’s assertion of Freud as an EST/INFP for that of my own assessment of Freud as an ISTJ. In that case, one may also remark that ISTJs and ENFPs are often attracted to each other. The case of Agathon (ENFP) and Pausanias (ISTJ), as featured in Plato’s Symposium, presents a classic case of such a pairing.

No matter what perspective one employs, however, a manifest duality emerges in the union of Freud and Empedocles, Vienna and Agrigentum, of duty and idiosyncrasy and of the sepulchral with the vivacious which together form components that attract and repulse each other as being themselves exemplars of Love and Strife, Eros and Thanatos. And none can deny the attraction exerted over the psyche by its own inferior dispositions.

References

Askay & Farquhar: Apprehending the Inaccessible Northwestern University Press 2005

Baron-Cohen: Zero Degrees of Empathy Penguin 2012

Berecz: All the Presidents’ Women Humanics 2000

Freeman et al.: Clinical Applications of Cognitive Therapy Springer 2004

Gay: A Life for Our Time W.W. Norton & Co. 1988

Graham: The Texts of Early Greek Philosophy vol. I Cambridge University Press 2010

Homans: Jung in Context University of Chicago Press 1995

Kaufmann: Discovering the Mind vol. III Transaction Publishers 1992

Kernberg: Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism Jason Aronson 1975

Lachman: Jung the Mystic Penguin 2010

Malcolm: In the Freud Archives New York Review Books Classics 2002

Mazlish: The Leader, the Led, and the Psyche Transaction Publishers 2013

McWilliams: Psychoanalytic Diagnosis Guilford Press 2011

Millon et al.: Personality Disorders in Modern Life Wiley 2004

Millon & Grossman: Overcoming Resistant Personality Disorders Wiley 2007

Nagy: Philosophical Issues in the Psychology of C.G. Jung SUNY Press 1991

Nietzsche: Beyond Good and Evil Cricket House 2012

Noll: The Jung Cult Fontana Press 1995

Odajnyk: Archetype and Character Palgrave Macmillan 2012

Roazen: How Freud Worked Jason Aronson 1977

Russell: History of Western Philosophy Routledge 2013

Vamvacas: The Founders of Western Thought Springer 2009

Waterfield: The First Philosophers Oxford University Press 2009

Young, Klosko & Beck: Reinventing Your Life Plume 1994

NOTES

[1] Plutarch: Moralia §7

[2] Freud jokingly referred to himself as having elements of a Compulsive style, stating in a letter to Jung that: “If a healthy man like you regards himself as an hysterical [Histrionic] type, I can only claim for myself the ‘obsessional’ [Compulsive] type, each specimen of which vegetates into a sealed-off world of his own” (Freud: Personal Letter to Jung September 1907). Likewise, Theodore Millon would confirm that Freud had a Narcissistic style in his assessment (Millon: Personal correspondence, 2013).

[3] Millon & Grossman: Overcoming Resistant Personality Disorders p. 257

[4] This observation can also lend an insight into the nature of the famous episode regarding Freud’s reluctance to reveal the full details of his personal life to Jung. In an interview given in 1959, Jung first confides in the interviewer that he knows what troubled Freud in his dreams, but then histrionically refuses to discuss their content. (Why not just keep his mouth shut the whole time then?) Now, an imaginative crowd, such as the one that tends to be drawn to psychology, is bound to envisage that Freud – the man with the many bizarre theories who wrote so much about sex – must have had the most depraved dreams imaginable. But since aberrant dreams and theories represented no moral problem for Freud (indeed he saw them as the legitimate and unavoidable consequences of repressing one’s immediate needs), it seems more likely that the fact that Freud could not divulge was that he had an affair with his sister-in-law in 1898. There are quite a number of reasons that corroborate this conjecture. Given Freud’s unrelenting standards, and his tendency to focus on acts rather than thoughts, it is much more in line with Freud’s personal psychology that he would have found the physical act of being unfaithful (i.e. unable to control himself) an unforgivable error, whereas the deviant thought was entirely permissible, indeed natural. If we assert that Freud had a Compulsive personality style, we should note that the whole issue of control (and particularly self-control) is central to this style. The Compulsive is always wary of falling short of his own unrelenting standards, forever assailing himself for not being “good enough.” To maintain a sense of control over his life, the Compulsive overworks himself and pushes himself to meet every obligation in as conscientious a manner as possible. His self-esteem comes from holding himself to a high standard. Any act (not thought) that falls short of this standard construes the self as irresponsible and deserving of condemnation (the critical parent rears its head again here). In this way, Compulsives go through inordinate amounts of self-criticism. Indeed, as the psychologist Nancy McWilliams has said, Compulsive personalities define moral rectitude in terms of exhibiting control of their own behavior (McWilliams: Psychoanalytic Diagnosis p. 300). I conjecture that this fear of falling short of his own unrelenting standards was the reason Freud refused to confide in Jung. Though of course, should Freud have admitted to an affair, it would hardly have posed a moral problem in the eyes of the erotically licentious Jung.

Some further points on this matter:

- According to Jung (not always the most reliable source when it comes to historical facts), Freud’s stated excuse for refusing to elaborate on the details of his personal life was: “I cannot risk my authority.”

- According to Gary Lachman, the details of Freud’s personal life that he could not reveal to Jung on that occasion had something to do with his sister-in-law. (Lachman: Jung the Mystic, Chapter 4.)

- Lachman also claims that Jung never revealed anything about the nature of Freud’s dreams. (Lachman: Jung the Mystic, Chapter 4.) Strictly speaking, this is true, but Lachman seems unaware that Jung gave an interview in 1957 wherein he told the interviewer that during a visit to Vienna in 1907, Freud’s sister-in-law had confided in him that “Freud was in love with her” and that “their relationship was very intimate.” In the course of this same interview, Jung then proceeded to speak about the episode where Freud had supposedly refused to divulge the details of his personal life, having allegedly said that he could not risk his authority. Jung thus concluded in the interview that “it was my knowledge of Freud’s triangle that became a very important factor in my break with Freud.” (Jung, cited in Homans: Jung in Context p. 53n3) The phrase: “I cannot risk my authority” appears in both this interview and in Jung’s so-called biography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections. But MDR is not a reliable work.

- Against Jung’s testimony, however, we must interpose that Jung could easily have been projecting, given the numerous love-triangles that Jung habitually involved himself in. As he wrote to Freud before their break: “The prerequisite for a good marriage, it seems to me, is the license to be unfaithful.” (Jung: Personal Letter to Freud January 1910.)

- As the record of Jung’s statements on the matter shows, Jung was really quite indiscreet with Freud’s personal secrets. Freud was prudent not to trust him.

[5] Jung’s early statements on Freud’s type say both that Freud is extroverted (Psychological Types §91) and that his theory affords “the greatest role to Sensation” (Psychological Types §880). However, we are barred from postulating that Jung then considered Freud to be an ESP at the time, for in a later personal letter, Jung admits to having mistyped Freud, professing that: “Freud, then as later, presented the picture of extraverted thinker and empiricist” (Jung: Personal Letter to Ernst Hanhart February 1957). It would seem that Jung’s initial assessment of Freud’s type was some unquantified stripe of EST, which cannot be further elaborated with regards to the functions.

[6] These points inspired by Young, Klosko & Beck: Reinventing Your Life p. 296 ff.

[7] Freud, quoted in Kaufmann: Discovering the Mind vol. III pp. 46-47

[8] Millon et al.: Personality Disorders in Modern Life p. 232

[9] Albeit perhaps with some auxiliary Narcissistic elements as well, although these elements are not relevant to our purposes here.

[10] The Histrionic may resemble the Narcissistic personality in his need for admiration and approval. But as I note, the Histrionic morphologic organization is exceedingly fickle and flimsy. On closer inspection, while the Narcissist’s morphologic organization will also be found to be flimsy (“spurious” in Millon’s terminology), the Narcissist is nevertheless episodically coherent, i.e. it is only when observed over a longer period of time that the Narcissist reveals his spurious internal organization. By contrast, it is generally quite obvious that the Histrionic is incoherent, even from moment to moment. In conclusion, the Histrionic and the Narcissist do indeed resemble each other, but the salient difference is the degree of integration and organization within the psyche – the Narcissist is not quite as flighty and self-contradictory as the Histrionic.

[11] McWilliams: Psychoanalytic Diagnosis p. 322

[12] Millon et al.: Personality Disorders in Modern Life p. 298

[13] McWilliams: Psychoanalytic Diagnosis p. 313

[14] Nietzsche: Beyond Good and Evil §28: “Lessing is an exception, owing to his histrionic nature, which understood much, and was versed in many things … Lessing loved also free-spiritism in the tempo, and flight out of Germany.”

[15] Russell: History of Western Philosophy §1.1.6

[16] Shengold, quoted in Malcolm: In the Freud Archives p. 82

[17] McWilliams: Psychoanalytic Diagnosis p. 296

[18] In reality, though, the transaction between the Compulsive and the Histrionic is rarely that simple, namely because Histrionics tend to be deceptively and surprisingly resourceful. But that is a discussion for another essay.

[19] Kaufmann: Discovering the Mind vol. III p. 398

[20] Kernberg: Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism p. 311

[21] Berecz: All the Presidents’ Women, chapter 4

[22] Freeman et al.: Clinical Applications of Cognitive Therapy p. 261

[23] The various kinds of empathy (e.g. affective and cognitive) may be read about in Baron-Cohen: Zero Degrees of Empathy.

[24] Jung: Personal Letter to Freud October 1907 cf. Homans: Jung in Context p. 56 ff.

[25] Odajnyk: Archetype and Character pp. 64-65

[26] An interesting aside here is that Jung identified himself as a Ti type throughout his life, whereas almost everyone who has studied him (including some of his closest associates) have come to the conclusion that he was an Ni type. Could Jung have been projecting?

***

Image of Freud in the article commissioned from artist Francesca Elettra.