Academically reviewed by Dr. Jennifer Schulz, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology

Reading the Mind in the Eyes (RMET) Test

The "Reading the Mind in the Eyes" test, developed by Professor Simon Baron-Cohen and his team at the University of Cambridge, assesses a person's ability to recognize emotions from subtle facial cues. Often used in psychological and autism research, the test presents images of eyes and asks participants to identify the emotion, offering insight into theory of mind capabilities.

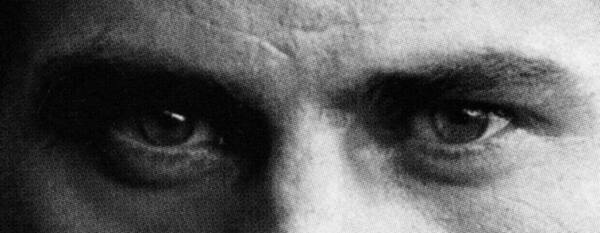

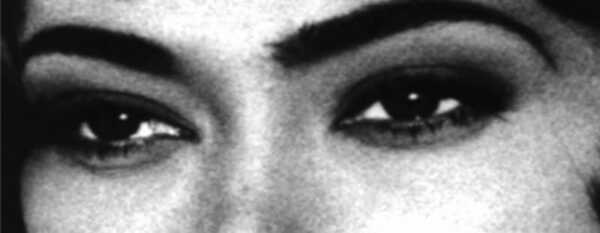

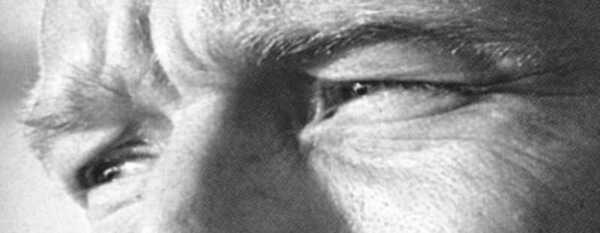

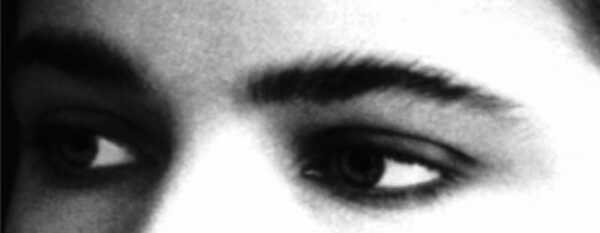

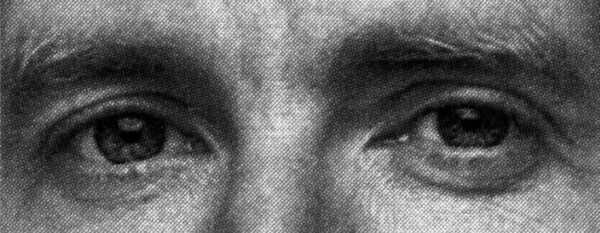

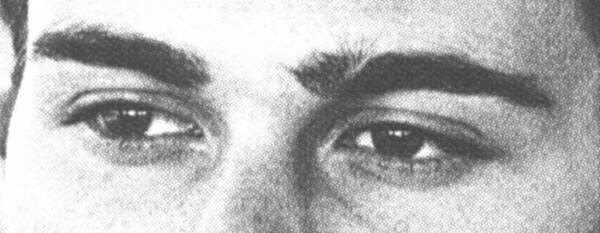

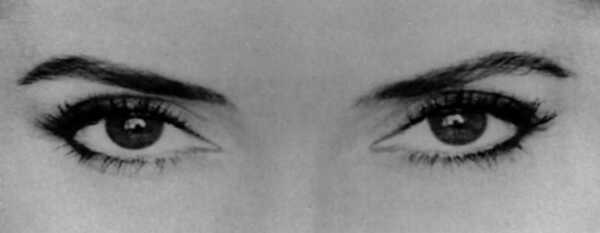

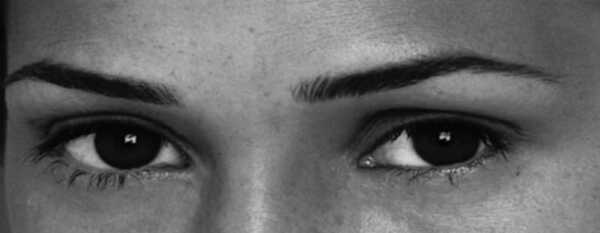

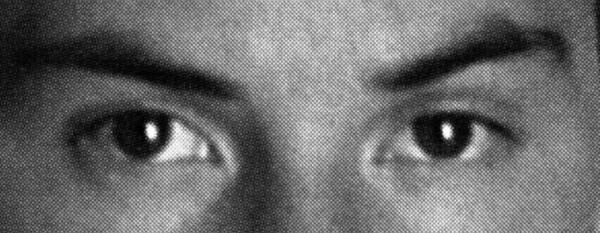

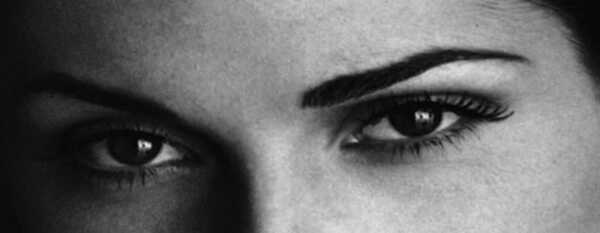

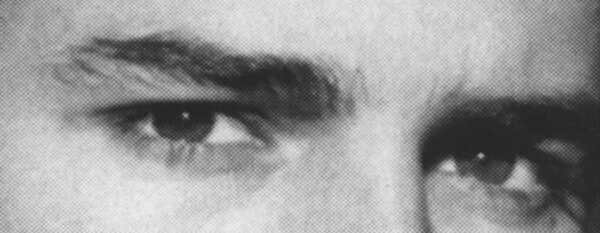

Question 1 of 36

NEXT

The Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET) is a widely recognized psychological measure developed to assess individual differences in theory of mind—the ability to understand and infer others’ thoughts, emotions, and intentions. Originating from the research of Professor Simon Baron-Cohen and his colleagues at the Autism Research Centre, University of Cambridge, the test was initially introduced in the late 1990s. It was designed primarily to investigate social cognition impairments in individuals with autism spectrum conditions, particularly in adults of normal or high intelligence.

The test is composed of a series of black-and-white photographs showing only the eye region of different actors and models. For each image, the participant is asked to choose which of four mental state terms best describes what the person in the photo is thinking or feeling. The options typically include nuanced emotional or cognitive descriptors such as "skeptical," "embarrassed," "nervous," or "contemplative." This format aims to tap into subtle, high-level interpretive abilities beyond basic emotion recognition.

Baron-Cohen and his team initially created a child version of the RMET, but it was the adult version, revised and standardized in 2001, that gained significant traction in both clinical and research settings. The revised version includes 36 items and has been used to study populations ranging from neurotypical adults to individuals with autism, schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, and other conditions affecting social cognition.

The RMET is grounded in the concept of theory of mind, or “mentalizing,” which refers to our capacity to attribute mental states to ourselves and others. While typical development includes the natural acquisition of these skills early in life, individuals with autism often display delays or deficits in theory of mind, leading to challenges in understanding social cues and responding to others appropriately. The RMET serves as a window into these cognitive mechanisms by testing one’s ability to read complex mental states through minimal visual input.

Critically, the RMET does not measure intelligence, language, or memory directly, which makes it particularly useful in isolating social cognitive function. It has been translated into numerous languages and adapted for various cultural contexts, although some researchers have raised concerns about potential cultural bias and the test’s reliance on vocabulary and emotion-label comprehension.

Despite such limitations, the RMET remains one of the most commonly used instruments for assessing advanced social cognition. It has contributed to numerous studies investigating empathy, gender differences in emotional intelligence, and the neural correlates of social perception. Functional imaging studies, for example, have shown that performance on the RMET is associated with activity in brain regions involved in social cognition, such as the medial prefrontal cortex and the temporoparietal junction.

In summary, the RMET provides a simple yet powerful tool to assess how well individuals can interpret others' mental states from limited visual information. Its relevance spans clinical diagnosis, cognitive neuroscience, and developmental psychology.

References

- Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001). The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

- Baron-Cohen, S., Jolliffe, T., Mortimore, C., & Robertson, M. (1997). Another advanced test of theory of mind: Evidence from very high functioning adults with autism or Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(7), 813–822.

English

English  Español

Español  Português

Português  Deutsch

Deutsch  Français

Français  Italiano

Italiano  Polski

Polski  Українська

Українська  Русский

Русский  Türkçe

Türkçe  العربية

العربية  日本語

日本語  한국어

한국어  ไทย

ไทย  汉语

汉语  हिन्दी

हिन्दी  Bahasa

Bahasa